Since Richard Gombrich’s and Gananath Obeyesekere’s Buddhism Transformed, there have been very few urban anthropological studies in, or on, Sri Lanka. This is a striking omission, particularly considering how our cities and roads have grown since its publication and how pervasive urbanisation has become. Such developments should spur research into urban cultures, how these have been influenced, and shaped, by rural beliefs, and how rural beliefs themselves have been reconfigured by urban society.

That they have not is bewildering, moreso since most of the landmark anthropological studies in Sri Lanka – including Martin Wickramasinghe’s essays on culture and James Brow’s work of the Veddhas of Anuradhapura –underscored how urbanisation was dismantling the social fabric of the village. In their scheme, the village could not be viewed in isolation from the city, nor the city from the village. At the most basic level, yes, there was a clash of values between these two. But the one intruded on the other, shaped the other, and was shaped by the other. These linkages have never been properly studied.

That they have not is bewildering, moreso since most of the landmark anthropological studies in Sri Lanka – including Martin Wickramasinghe’s essays on culture and James Brow’s work of the Veddhas of Anuradhapura –underscored how urbanisation was dismantling the social fabric of the village. In their scheme, the village could not be viewed in isolation from the city, nor the city from the village. At the most basic level, yes, there was a clash of values between these two. But the one intruded on the other, shaped the other, and was shaped by the other. These linkages have never been properly studied.

Popular culture is to blame for this. Television dramas and films have been particularly guilty, reinforcing stereotypes about these two worlds. The 1980s, for instance, witnessed a deluge of TV shows that romanticised the village and presented the city as a malevolent entity against which it had to be protected. The opening up of the economy and the breakdown of the traditional order no doubt coloured these perceptions.

In these productions, the urban manifests itself as a haven of vice, vulgarity, and deception. Often it centres on a specific character. Sriyantha Mendis’s character in Dhamma Jagoda’s Palingu Menike is a case in point. When the story begins, he has supposedly returned from a Middle Eastern country. Wearing the dandiest shirts, donning sunglasses and a cowboy hat,carrying a flashy radio on his shoulders, he passes himself off as a sophisticated bon vivant, an eligible bachelor. The story ends with him being revealed as a fraud. The revelation serves a purpose: as in a Greek drama, it restores order and stability.

Perennial theme

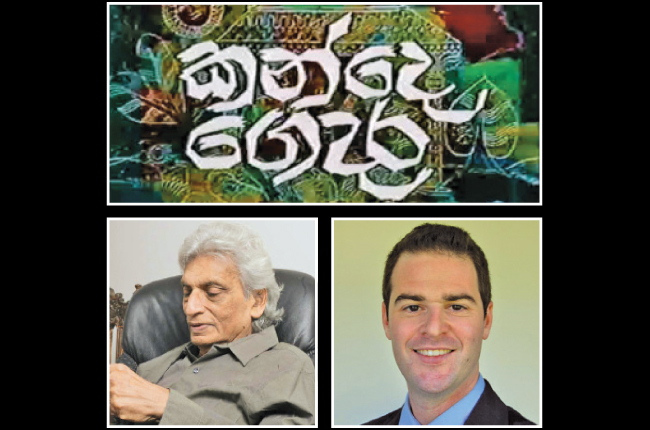

Palingu Menike was followed by a stream of other miniseries, all of which provide variations on this perennial theme. In Kande Gedara, a rural upper-class couple played by Rohana Baddage and the late Ramya Wanigasekara travel to the city to visit their children, played by Jayalath Manoratne and Kumari Perera. Manoratne has married into a well-to-do family and is leading a lavish lifestyle: his two children dote on Western culture, including Michael Jackson. Kumari, on the other hand, has married into more modest circumstances: her father-in-law, played by Cyril Wickramage, is a conman, though like Mendis’s character from Palingu Menike he pretends to be a cut above the rest.

It wasn’t just television serials, of course. Even films reinforced these stereotypes and divisions. In comparison to TV, however, they exuded some nuance. H. D. Premaratne’s Parithyagaya, Devani Gamana, Visidela, and Kinihiriya Mal, for instance, contrast the village with the city. But they do not portray the village as a haven of innocence and purity. Parithyagaya and Devani Gamana, in particular, criticise some of the more backward beliefs in Sinhala rural society, including the practice of checking a bride’s virginity after her first night. The city, in this scheme, becomes a modernising force: when the mother in Devani Gamana berates the protagonist after discovering she has failed to bleed, her husband, a schoolteacher, suggests this may be because she played basketball.

To be sure, these films were exceptions for their time. For every Sinhala film which critiqued rural beliefs, there were tens if not hundreds of other films which romanticised them; as Regi Siriwardena noted in his review of Shelton Payagala’s Malata Noena Bambaru – the first Sri Lankan film to openly depict homosexuality – even “art house” productions can reinforce stereotypes about the village and city that one would usually associate with commercial films. But though they were exceptional, they provided us with alternative readings of the city and the village, with more depth and nuance.

City and village

And yet, even these films draw a wedge between the urban and rural that makes it hardto appreciate how much the one has seeped into the other. I can think of only one Sinhala film, made after 1990, which explored intelligently the relations between these two worlds: H. D. Premaratne’s Seilama. That may be because it was written by Simon Navagattegama, whose stories criss cross city and village. How many other films like it can one point to? Very few. Sinhala popular culture, for the most, has depicted the village as a rural backwater in need of validation by the city, or a haven of innocence in need of protection from it. In either case, the one exists apart from, and independent of, the other.

We urgently need a new way of looking at these two worlds which does not frame them as different entities. The work of Steven Kemper (advertising in Sri Lanka), Garrett Field (Sinhala music in the 20th century), and Anne Sheeran (baila) have explored the many ways in which urban culture has been transmogrified by rural values. These are useful primers. Scholars should take such studies forward, to help us deconstruct the rural underside of the urban. As a discipline, urban anthropology is best fitted for this task.

It’s interesting how rural and supposedly superstitious beliefs have found their way to the most sophisticated spaces. Near the intersection at Horton Place the other day, I came across, of all things, a Pahan Maduwa. The Pahan Maduwa is, of course, used to symbolise a beginning, to invoke divine blessings. Such elements are cropping up everywhere in the cities, even at the heart of Colombo. Against that backdrop, does it make sense to speak of the rural without invoking the urban, or vice-versa? Probably not.

Uditha Devapriya is a writer, researcher, and analyst who writes on topics such as history, art and culture, politics, and foreign policy. He is one of the two leads in U & U, an informal art and culture research collective. He can be reached at [email protected].