First impressions matter. Especially when it comes to the first line in a novel. Even more so, when that line is a translation and belongs to Albert Camus’s “L’Étranger.”

First impressions matter. Especially when it comes to the first line in a novel. Even more so, when that line is a translation and belongs to Albert Camus’s “L’Étranger.”

History has it Camus’s first sentence in “L’Étranger, “Aujourd’hui, maman est morte” was first translated by Stuart Gilbert, a British scholar, in 1946 as “Mother died today.” In 1982 both Joseph Laredo and Kate Griffith wrote new translations of “The Stranger,” but kept Gilbert’s first sentence unchanged.

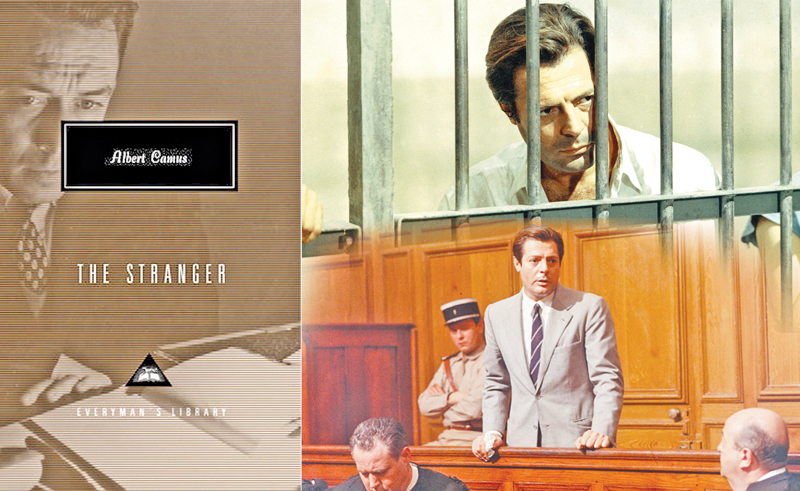

Camus’s 1942 novel L’Etranger, set in Algeria, is the story of how his absurd hero, Meursault, guns down an Arab on the beach and is subsequently sentenced to death by the Franco-Algerian state for refusing to express regret. The book is a philosophical exploration of what Camus called “the tender indifference of the world” and is synonymous with existentialism, even though Camus thought otherwise. Hailed as the “sparest of novels,” “The Stranger” is a story that has been analysed at various levels for its characters and motives, its sketchy female figures, the passivity of the silent Arab. Yet, in recent times, it is the famous opening line and its different versions in English translations that has taken up more space than the novel itself.

As critic Ryan Bloom points out, for forty-two years, most readers of “The Stranger,” were introduced to Meursault through the detached formality of his statement, translated to English by Stuart Gilbert, as “Mother died today.” There is little warmth, closeness or love in “Mother,” a static, archetypal term we hardly ever use in our daily conversations to describe a person who is close to our heart. Even if otherwise, we never call our call our dog, ‘Dog’ or husband, “Husband.” When translators force these words out of Meursault the reader can’t help but see him as someone who is not close to the woman who gave him birth.

Bloom wonders what it would have been like, if the opening line had read, “Mommy died today”? “How would we have seen Meursault then? Likely, our first impression would have been of a child speaking. Rather than being put off, we would have felt pity or sympathy. But this, too, would have presented an inaccurate view of Meursault. The truth is that neither of these translations—“Mother” or “Mommy”—ring true to the original. “The French word maman hangs somewhere between the two extremes: it’s neither the cold and distant “mother” nor the overly childlike “mommy.” In English, “mom” might seem the closest fit for Camus’s sentence, but there’s still something off-putting and abrupt about the single-syllable word; the two-syllable maman has a touch of softness and warmth that is lost with “mom.”

Thankfully, in 1988, American translator Matthew Ward in his translation of “The Stranger”, made a single word change in the opening sentence. He reverted “Mother” back to Maman.

Bloom says, it seems Ward, did the only logical thing: nothing. He left Camus’s word untouched, translating the famous first line as, “Maman died today.” Bloom concedes Ward introduces a new problem: now, right from the start, the reader is faced with a foreign term, with a confusion not previously present. Yet, at the same time, Ward’s translation is clever. Here is why.

Bloom says, it seems Ward, did the only logical thing: nothing. He left Camus’s word untouched, translating the famous first line as, “Maman died today.” Bloom concedes Ward introduces a new problem: now, right from the start, the reader is faced with a foreign term, with a confusion not previously present. Yet, at the same time, Ward’s translation is clever. Here is why.

As Bloom explains, “first, the French word maman is familiar enough for an English-language reader to understand. Around the globe, as children learn to form words by babbling, they begin with the simplest sounds. In many languages, bilabials such as “m,” “p,” and “b,” as well as the low vowel “a,” are among the easiest to produce. As a result, in English, we find that children initially refer to the female parent as “mama.” Even in a language as seemingly different as Mandarin Chinese, we find mma; in the languages of Southern India we get amma, and in Norwegian, Italian, Swedish, and Icelandic, as well as many other languages, the word used is “mamma.” The French maman is so similar that the English-language reader will effortlessly understand it.”

Bloom also points out that as the years pass, new generations of readers will grow more and more removed from the historical context of Camus’s novel. Thus, utilizing the original French word in the first sentence rather than any of the English options also serves to remind readers that they are in fact entering a world different from their own. While this hint may not be enough to inform the younger readers that, for example, the likelihood of a Frenchman in colonial Algeria getting the death penalty for killing an armed Arab was slim to nonexistent, at least it provides an initial allusion to these extra-textual facts.

Finally, and perhaps most important, the reader will harbor no preconceived notions of the word maman. He or she will understand it with ease, but it will carry no baggage, it will plant no unintended seeds. The word will neither sway the reader to see Meursault as overly cold and heartless nor as overly warm and loving. And while some of the word’s precision is indeed lost for the English-language reader, maman still gives them a more neutral-to-familiar tone than “mother.”

For all this, in yet another translation, Joseph Laredo renders the opening as: “Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.” To this line, Sandra Smith in her translation, adds a possessive pronoun: “My mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.” Some critics believe Smith restores Meursault, to a dislocating state of shock as opposed to the cold indifference of the previous version.

Yet, in view of Meursault’s cold indifference, one wonders which translation can be hailed as the best. For, there is no argument of Meursault’s apathy. “That evening Marie came by to see me and asked me if I wanted to marry her,” he recounts. “I said it didn’t make any difference to me and that we could if she wanted to.”

While the debate rages on the best possible translation of one simple sentence, others like Alice Kaplan, in her book, “Looking for ‘The Stranger,’” tells “the story of exactly how Camus created this singular book.” According to Kaplan it was Camus’s time as a court reporter for the anticolonial newspaper Alger-Républicain in the late 1930s that gave him a front-row seat in “a theater for the tensions and dramas of a society structured on inequality,” and provided him specific material for “The Stranger.”

Through Kaplan’s descriptions of Camus’s childhood which was largely “silent”, as he grew up with his mother and uncle, who were both deaf, it is easy to see similarities with his writing style in “The Stranger,” the words reduced to a minimum, largely referencing objects, never abstractions.

All in all, while for most readers the first line of “The Stranger” in translation, remains the most memorable, for yours truly the best line in the book, the line that speaks of the mask-wearing, sanitizer overloaded, one and a half meter distance world of ours at present, is the simple, yet poignant sentence; “After awhile you could get used to anything.”

****

The Stranger’s Untold Story

According to M. Arbeiter Camus began his writing career during the ascension of Germany’s Third Reich and endured the occupation of his Paris home and the surrounding areas. He was forced to flee the French capital in 1940, relocating to the cities of Clermont-Ferrand and Lyon before ultimately returning to his native Algeria. During this period, Camus got married and then almost immediately lost his job, but held tight to his “Stranger” manuscript through the years of travel.

THE BOOK WAS A HIT IN ANTI-NAZI CIRCLES.

As “The Stranger” was published in France at a time when the country’s print output suffered from German censorship, Nazi officials inspected the novel for potential instances of defamation to the Third Reich. Although Camus’s work passed muster with Hitler’s regime, “The Stranger” was immediately popular among anti-Nazi Party activists. The antiestablishment sensibilities of the story were subtle enough to sail past the censors, but the subtext read loud and clear to those harboring enmity from an increasingly powerful Germany.

CAMUS DIDN’T LIKE WHEN PEOPLE CALLED THE NOVEL “EXISTENTIALIST.”

Not only did Camus resent comparison to the style and philosophy of Sartre (a man he otherwise respected), the author contested the idea that he or his works might be categorized under the umbrella of existentialism. The writer instead indicated that his works were nearer absurdism, but he also confessed to being annoyed by the word.