Fiction is life. Life is fiction. So I keep learning every day. It wasn’t long ago that in one of my novels I wrote about a journalist who goes to interview an academic, and falls in love with him. By the time the story ends they are on the path to a happy marriage. A few minutes ago, I found out such encounters are not restricted to the pages of novels only but occur in real life too. In 1994 Ian McEwan met his future wife when a journalist called Annalena McAfee came to interview him for the ‘Financial Times’. Both had been married before; he had two sons and two stepdaughters. But true love triumphed. Today they lead a fairy-tale life, writing from dawn to dusk creating worlds from words in a renovated seventeenth-century brick-and-flint cottage, situated on nine acres of land in Cotswolds. Their garden - covered in daisies, walnut trees, a lake and everything else enchanting resembles paradise found.

Fiction is life. Life is fiction. So I keep learning every day. It wasn’t long ago that in one of my novels I wrote about a journalist who goes to interview an academic, and falls in love with him. By the time the story ends they are on the path to a happy marriage. A few minutes ago, I found out such encounters are not restricted to the pages of novels only but occur in real life too. In 1994 Ian McEwan met his future wife when a journalist called Annalena McAfee came to interview him for the ‘Financial Times’. Both had been married before; he had two sons and two stepdaughters. But true love triumphed. Today they lead a fairy-tale life, writing from dawn to dusk creating worlds from words in a renovated seventeenth-century brick-and-flint cottage, situated on nine acres of land in Cotswolds. Their garden - covered in daisies, walnut trees, a lake and everything else enchanting resembles paradise found.

Life though, hadn’t always been this good for McEwan. As he revealed in an interview with the Paris Review, his father, David McEwan was a hard-drinking man. “My earliest recollections are of weekday idylls with my mother interrupted at weekends by the loud appearance of my father, when our tiny prefabricated bungalow would fill with his cigarette smoke...Both my mother and I were rather frightened of him. She grew up in a small village near Aldershot and left school at fourteen to go into service as a chambermaid. Later she worked in a department store. But for most of her life she was a housewife, with her generation’s fierce pride in the orderliness and gleam of the family home.”

He describes himself as a quiet, pale, dreamy, boy shy and average in class and very attached to his mother. “I was an intimate sort of child who never spoke up in groups. I preferred close friends,” says McEwan. His parents were keen for him to have the education they themselves never had. They weren’t able to guide him towards particular books, but they encouraged him to read, which he did, randomly and compulsively. At boarding school in his early teens he had more direction. “When I was sixteen I came under the influence of a very effective English teacher, Neil Clayton, who encouraged wide reading and had the knack of making writers like Herbert, Swift, and Coleridge seem like living presences” he recalls. “I began to think of literature as a kind of priesthood that I would one day enter.”

After he entered the University of Sussex, however, he abandoned the priesthood idea. Upon his graduation he came across a new course at the University of East Anglia, which would allow him to write fiction along with the academic work. He phoned the university and amazingly got straight through to Malcolm Bradbury. But Bradbury said, Oh, the fiction part has been dropped because nobody has applied. This was the first year of the program. And McEwan then said, Well, what if I apply? He said, Come up and talk to us and we’ll see.

“It was a wonderful stroke of luck,” he rejoices. He became the first student in the MA degree for creative writing. “That year—1970—changed my life. I wrote a short story every three of four weeks, and I’d meet Malcolm in a Norwich pub for half an hour. Later on I met Angus Wilson. They were both generally encouraging, but they did not interfere at all, and gave no specific advice. That was perfect for me.”

In 1971 Transatlantic Review published his first story. Sometime later his name was on the cover of the Review along with Günter Grass, Susan Sontag, and Philip Roth. “I was twenty-three and I felt like an impostor, but I was also very excited.” Today he is the author of fourteen novels, including Atonement (2001), Enduring Love, (1997), and Amsterdam (1998), which was awarded the Booker Prize. In 2008, The Times featured him on their list of “The 50 greatest British writers since 1945” and The Daily Telegraph ranked him number 19 in their list of the “100 most powerful people in British Culture.”

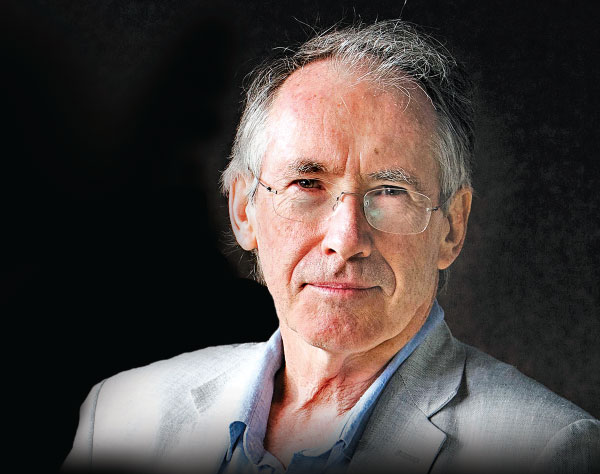

Adam Begley who interviewed McEwan for the Paris review says Ian McEwan is “A trim, handsome man, careful, exacting, and (for a writer) curiously un-neurotic.” According to the New Yorker he has an old-fashioned talent for creating suspense. “McEwan said that one of his goals was to “incite a naked hunger in readers.” He discusses his technique reluctantly, as if he were a chemist guarding a newly filed patent. “Narrative tension is primarily about withholding information,” is how he describes his writing style.

Critics say “McEwan is a connoisseur of dread, performing the literary equivalent of turning on the tub faucet and leaving the room; the flood is foreseeable, but it still shocks when the water rushes over the edge. At moments of peak intensity, McEwan slows time down—a form of torture that readers enjoy despite themselves.” In “Saturday” for example, he keeps the reader jangled for nearly forty pages, wondering along with Perowne if an airplane descending on London has become a terrorist missile. Martin Amis says, “Ian’s terribly good at stressed states. There’s a bit of Conrad that reminds me of Ian. It’s ‘Typhoon,’ when the captain is heading into this terrible storm and Conrad is in the position of first mate. Going into the captain’s cabin, he notices that the ship is yawing so that the captain’s shoes are rolling this way and that across the floor, like two puppies playing with each other. You think, Wow, to keep your eyes open when most people would be closing theirs. Ian has that. He’s unflinching.”

Asked about his writing process McEwan explains, “I have a large green ring-bound book—deliberately large so I don’t carry it around too much—that lives on the desk, and I doodle in it...There’s a phrase that the English critic and short story writer V.S. Pritchett used: “determined stupor.” A determined stupor is required in a novelist. You need silence and this kind of mental rambling out of which things begin to emerge. Characters walk to you as through a mist. Certain phrases require unwrapping. Sometimes, for example, I’ll write an opening paragraph that I know I’ll never have to complete, but knowing that I don’t have to continue it liberates me, and that way I trick myself into writing 500 or 600 words.”

McEwan also says he loves solitude. “Solitude is one of the great privileges of civilization. I don’t need it massively; I just need it during the day. Christopher Hitchens once said to me that he thought happiness was writing all day knowing that you are going to be in the company of an interesting friend in the evening, and I think that about gets it. That’s perfection. If from nine o’clock in the morning until seven the day’s entirely your own, and then you’re going to take a shower and go downtown and be stimulated in conversation with food and nice wine, you are riding one of civilization’s lovely waves.”

And yet, he is always available for his children. Here’s how he reserves time for them while also getting the solitude he needs to write. “The key to that is to always have your study door ajar so your children can wander in and out and think there’s nothing special about it. They’ll ignore you until they need you. If you want privacy, the paradoxical answer is to remain constantly available.” In spite of all the success he has achieved so far, McEwan thinks he is still in search of his best work. He confesses: “ I mean, I could be completely delusional. There has to come a point in your life when your best work is behind you.

But you need to keep alive the illusion that it’s still in front of you.”

Ian McEwan Quotes

01.Falling in love could be achieved in a single word—a glance.

02.True intelligence requires fabulous imagination.

03.The moment you lose curiosity in the world, you might as well be dead.

04.Not being boring is quite a challenge.

05.Reading groups, readings, breakdowns of book sales all tell the same story: when women stop reading, the novel will be dead.

Add new comment