In February, one-and-a-half years after Parliament passed the legislation to do so, President Maithripala Sirisena appointed commissioners to the Office of Missing Persons (OMP). The OMP was the first pillar of the unity government’s reconciliation agenda.

Official estimates put the number of disappeared people in Sri Lanka at around 20,000. Many went missing during the final stages of the war in 2009 and in the subsequent IDP camps, while families in the South also have memories of white vans and kidnappings during the two JVP insurrections. The OMP’s eight commissioners are tasked with tracking down information for the surviving families on what happened to their lost loved ones.

Attorney Saliya Pieris, PC, is the Chairperson of the OMP. He’s a former member of the country’s Human Rights Commission and a respected fundamental rights lawyer. He sat down with the Daily News this week to discuss setting up the new body, and its plans for the future.

Q: The Office of Missing Persons first met early this month, and last week the commissioners had their first public meeting with relatives of the disappeared. Can you tell me about that meeting?

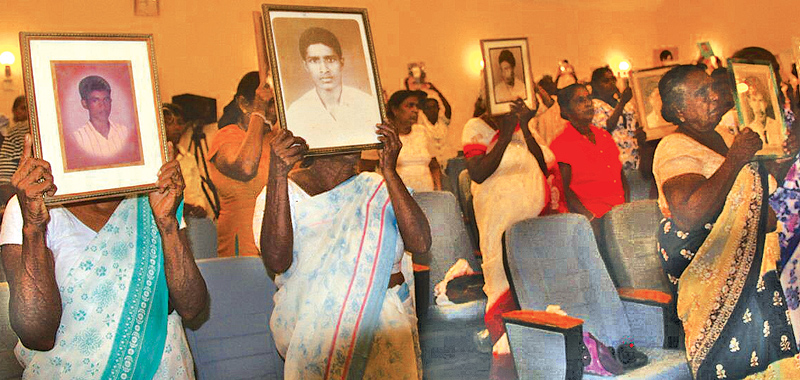

A: Yes, actually we were invited to that meeting by an organization called the Families of the Disappeared, which is part of the Right to Life movement. They invited me, as the OMP Chairman, and the commissioners for a meeting with the family members of the disappeared. So there were people from different parts of the country whose relatives disappeared during different conflicts, like the 1987–1989 conflict as well as the North-Eastern conflict. There were also some families of members of the armed forces, those who are ‘Missing in Action’.

They wanted to share their experiences and their views, and they invited us for that. But over the next few weeks and months, we will reach out to the different families of the disappeared, in the North and East as well as in the South. We will do that after we have done some planning, so we can share with them what we hope to do.

They wanted to share their experiences and their views, and they invited us for that. But over the next few weeks and months, we will reach out to the different families of the disappeared, in the North and East as well as in the South. We will do that after we have done some planning, so we can share with them what we hope to do.

Q: Right now is there any formal structure for families who wish to submit a complaint?

A: There isn’t. Because this is an entirely new office. The first step is to establish the physical office, as well as to recruit staff. So for the moment we have appointed a Secretary, M.I.M. Rafeek, who is a former Secretary to the Ministry of National Economy. We will be starting from a temporary office in Nawala, in the first part of April. We are in the process of getting the approvals to recruit certain temporary staff, and we will, in the next month or two, be finalizing our organization structure.

Q: How many staff are you looking to hire?

A: We have not yet decided on the numbers, but there are several units which are mandated by the law. There is the tracing unit, the victim and witness protection division, the administration division, and other divisions which we will be looking at to create.

Q: Would the first office, in Nawala, only be serving the Colombo area? Is there a plan to have regional offices?

A: No, that would be more temporary, just an outfit to get the process going. We plan to have regional offices, but those divisions are not yet finalized. The long-term plan is to have regional offices, of course, in the North and East, but also in other areas as well.

Q: Is there a simple, ideal vision of how the OMP will operate that you are pitching to families now, many of whom have waited so long for a mechanism like this?

A: We do not want to impose a structure on the families. We will go to the families, and we will ask them also for their views on what they want. We feel that that the consultation process is important, because the families should have the sense that this belongs to them and is not something that is imposed from the top. I think that’s important, because sometimes people feel that the state is imposing things and that this is not really what they want. So we are sensitive to the fact that there are a lot of families, especially in the North and East, who are skeptical of the OMP. We have to acknowledge that. It will be our challenge to create confidence. Having said that, there is not going to be a quick fix. We have to understand that this is going to take a while, because it involves establishing the structures, recruiting the right staff, and then looking at the various instances of the disappeared. And there are thousands. So this is a long-term effort, but in the short term, we are doing whatever we can do alleviate the suffering of the people.

Q: Do you think there is enough independence for the OMP in the Act, so that the institution can live on through successive governments without political influence?

A: The Act gives the institution independence, somewhat on the lines of the Human Rights Commission Act. Of course the difference between the OMP and the Human Rights Commission is that the Commission is also given a Constitutional provision. But I think the independence given is sufficient to perform the task.

Of course, having said that, political will is also very important if the work of the OMP is to be successful. The political will of the government is absolutely necessary, because we need the cooperation of other segments of the state to do our work.

Q: In early statements, you have asserted that the OMP is only a ‘fact-finding’ body, that it’s not a court of law. But obviously some of the findings regarding enforced disappearances might have criminal implications and should be taken to court. How will you navigate this tension?

A: Our function is not to punish. The law specifically says that the findings of the OMP cannot be used in any criminal or civil proceeding. They cannot be used as evidence in a criminal proceeding. However, if in the course of the OMP’s investigation, it is revealed that there is something that is a violation of criminal law, the OMP has the discretion, and it is important to emphasize discretion, to refer it to the prosecutorial authority. Then it is up to the investigating or prosecutorial authority to investigate afresh. We, the OMP, do not have punitive powers.

Q: How are you picturing the end result of an OMP investigation? Will it be a document of fact handed over to families?

A: No, it will not be a document only. We can make proposals about practical aspects like what sort of reparation should be given to the victims and their families. What other measures can be done for their welfare, for instance. We intend to give them psychosocial support as well. Many families don’t want just a document, they want something more. They want to know the fate of their loved one, what happened to him or her. Wherever possible, we will inform the families. But beyond that, there is also the making of recommendations for the alleviation of suffering.

The OMP is also empowered to make recommendations for the non-recurrence of disappearances. Disappearances should not happen, and what can we do to ensure this? We are also thinking about memorialization of the disappeared.

Q: When do you think the office will officially begin its investigative work?

A: In the first week of April we will be in a new office, which is on the first floor of the Ministry of National Reconciliation in Nawala. But afterwards we will shift to our permanent office. We have already started discussions and started planning.

Q: The OMP has always been hounded by two types of criticism. On one side you have the families of the disappeared, especially in the North and East, who say they didn’t feel heard in the crafting of legislation, that they weren’t involved in the process, that they don’t like that one of the commissioners is a former member of the military, and so they don’t have faith or trust that you can deliver what they’re asking for. On the other side, the criticism is that you’re going after the ‘war heroes’, you’re going to tarnish Sri Lanka’s reputation, and that there are OMP commissioners who have spoken against the government of Sri Lanka’s human rights record. So they don’t trust it for those reasons. How do you feel sitting in the middle of this? Do you feel a need to address either side?

A: Of course, this is quite natural. When we assumed office we were under no illusion that this would be the response. We fully understand the scepticism among the families of the disappeared. However, allegations against individual members are unreasonable. There’s no basis for it. The members of the OMP are diverse. We have a member whose husband disappeared. We have another representative from the North, and then we have the retired legal advisor to the military. It’s a diverse membership and I think they’re all important elements for the work of the OMP.

When we speak about the disappeared and missing, what I think both sides of the equation forget is that there are the disappeared and missing in the North and East, and there are the disappeared and missing in the rest of the country: the hill country, the Southern areas.

There are enforced disappearances, not only in the aftermath of the North-East conflict, but which are totally independent from that. Then you have the members of the Sri Lankan armed forces who are missing in action, and their families want to know what happened to them.

So the criticism is not unexpected, but we have to carry on, according to our mandate which has been given by Parliament.

Q: So just in your first month you’ve started hearing from the different people you will be interacting with. Do you think most of the cases you’ll be taking on will be from the North and East, from the end of the war?

A: We will ensure that we will consider the disappeared from all sectors. We expect a substantial portion from the North and East, but also a substantial portion from the rest of the country.

Q: In some cases, like the JVP insurrection of 1971, families have been waiting decades without answers about the loss of their loved ones. Have you met people who are still looking for information about their lost family members from so long ago?

A: Yes, I have. Among the people we met of the families of the disappeared, there were people from the North and East, but also those whose children or husbands had disappeared during the 1987–1989 conflict.

They are still looking for answers.

One person who spoke to me said that in his village, in the central area, there were dozens who had disappeared. One person told me that all his brothers had disappeared. He’s still looking for answers. I spoke to a Muslim woman from Colombo whose son had disappeared, a Tamil lady whose son had disappeared.

There were several older women, probably in their 70s, with photographs of their children. This problem, of the disappeared and missing, it’s such a human problem. People have to understand this. People want closure. And I think that is the duty of the country, to recognize that these disappearances happened, and there must be closure, and there must be some form of reparation for the families of those who are missing or have disappeared.

Add new comment