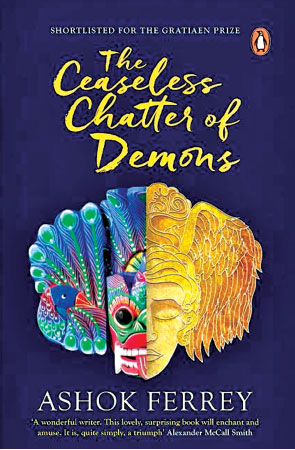

“The Ceaseless Chatter of Demons,” Ashok Ferrey’s new novel published by Penguin, India, has an impressive quote from Alexander McCall Smith on the front cover: “A wonderful writer. This lovely, surprising book will enchant and amuse. It is, quite simply, a triumph.” This is a handsome compliment, coming from such a renowned writer. Of the three novels written by Ferrey to date, this arguably is his best. Enchanting and amusing it is from the word go. When it comes to eloquent phrasing and poignant satire, Ferrey (one of Sri Lanka’s leading fiction writers) is in a class of his own. Whether he is writing short stories or novels, to produce irresistible page-turners is his unique gift, largely due to his flair for effortless storytelling. A hallmark of his writing is his incandescent wit.

All his books published to date (novels and short-stories) are very entertaining. They may not tackle complex social or psychological issues, but they do take a swipe at the false values and double standards espoused by privileged segments of Sri Lankan society, especially the westernized, upper-middle class. Here is an example (from “Demons”) of his breezy writing style and humorous prose: “I had thick curly black hair and flat features. But I had lustrous, velvety skin, even if it too was rather black for my mother’s refined Sanskritized tastes. My one great feature was my smile – it truly lit up the darkness I seemed to carry around with me – and it was surprisingly popular with the girls. Naturally, I smiled an awful lot. As expected, the only woman who was immune to this smile was my mother.”

“Demons,” though cosmopolitan in scope, is imbued with a strong local flavor. The imagery created through figurative language and witty dialogue is very Sri Lankan. The plot is woven round a series of events that occur after a young man from Bhairava Kanda (the one with ‘lustrous, velvety skin’) is packed off to Oxford University by his strong-minded mother, who is obsessed with the lost treasures of the erstwhile Kandyan Kingdom, not to mention various rituals associated with Bhairava Kanda sub-culture, such as demonry and necromancy. The sprawling old house she lives in (Mahadewala Walauwa) is a symbol of wealth and prestige. Legend has it that Bhairava Kanda (‘gnome mountain’) is where hundreds of young virgins were sacrificed to Bhairava, the four-headed Demon King, during the days of the Nayakkar Kings, the last rulers of Kandy.

While at Oxford he falls for the lovely young daughter of an Italian-American millionaire, a few years older than himself. A heady one-night stand produces an unexpected result: a shotgun marriage to which he has difficulty adjusting, so much so that he quits Oxford and goes to live with her in Putney, a district in south-west London. He tries to become a writer but fails to finish the book.

It is when the couple goes to Bhairava Kanda on holiday (late 2004) that various complications arise. The plot takes an unexpected turn as the spotlight shifts from the protagonist to the humble housemaid who, having endured a great deal of humiliation and abuse, decides to turn tables on the status quo. The manner in which she hijacks the story is an interesting feature of the plot.

The protagonist (Sonny), his overbearing mother (Clarice), his enigmatic wife (Luisa), and the lowly housemaid (Sita) comprise the core of the dramatis personae. The macho garden boy (Pandu), who displays an insatiable lust for Sita, adds an interesting dimension to the plot. So does the drag queen – a demon who emerges from the netherworld to check out the scene in Bhairava Kanda, where it is believed the ogre still resides (though he doesn’t howl for blood any more). All three novels by Ferrey are of the cross-cultural variety, but in “Demons” we see his gift for poetic imagery and artistic expression undergoing a complete metamorphosis from chrysalis to Lepidoptera. What we now see is a new kind of Ferrey blending luculent prose with expansive vocabulary to create colors, tones and textures every bit as delicate and enchanting as those of a Jezebel or a Sylphina Angel.

Through skillful use of a variety of literary devices such as metaphors, similes, idioms, symbolism, flashbacks and alternative viewpoints (omniscient and restrictive), the writer creates a sharp divide between modern, post-industrial British society and traditional, pre-industrial Sri Lankan society, with focus on the Bhairava Kanda sub-culture, symbolized by Clarice’s Weltanschauung – an infernal blend of prejudice, bigotry, superstition, greed and ruthless pragmatism. Even the drag queen is impressed by it.

Let us pause for a moment to recall Robert Knox, who provides a fascinating account of Kandyan culture in his book, “An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon.” Knox was of course an Englishman and his seminal work was published in 1681. This was more than a hundred years before the British conquest of Ceylon commenced. In “Demons” one can find examples of how the colonial powers (British, Dutch, Portuguese) collectively altered the course of Sri Lankan history.

Like Ferrey’s other two novels, this one also relies heavily on sub-text to capture the various shades and nuances of Sri Lankan culture. In this regard the author toys with the concept of morality, especially in the context of Bhairava Kanda sub-culture, where the lines between good and evil are blurred. A peculiar feature of the novel is that the person who impacts the reader most is a minor character (Sita) and not the protagonist. If there is a central theme, it is embedded somewhere in the book and is not easily accessible. But all in all, “Demons” is a winner, an excellent read.

Add new comment