One of the most fervent radicals of Hollywood, Oliver Stone is also one of the most sincere. Stone’s career began in 1978 when his screenplay for Alan Parker’s Midnight Express won him a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar. Midnight Express is, of course, not the best film with which one can assess Stone’s radicalism, particularly because its vision of Turks differs from Stone’s depictions of American soldiers and Vietnamese civilians in his later work. Yet Stone made a mark at a particularly crucial juncture in American film history.

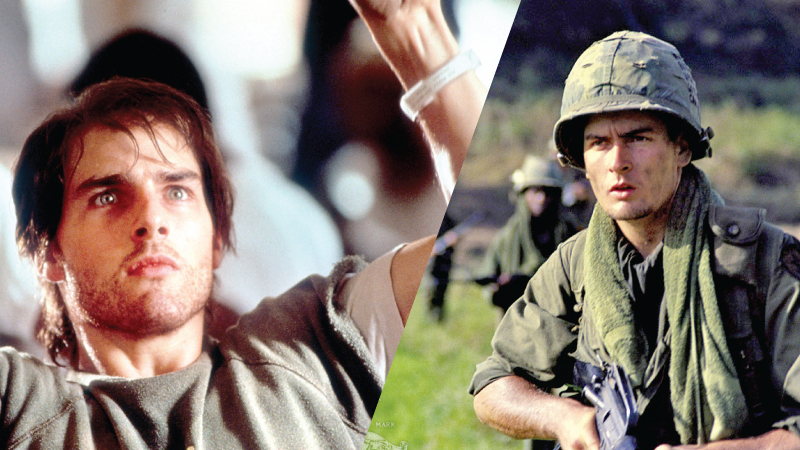

He is known, more than anything else perhaps, for his trilogy about the Vietnam War. Platoon, the first in the trilogy, won Best Picture and Best Director Oscars; the second, Born on the Fourth of July, won his Best Director, and gave Tom Cruise the best performance in his career. The third, Heaven & Earth, did not do much, but immediately following this trio he made Natural Born Killers, a stark indictment on the American media that is as ruthless as it is wry. He also directed JFK, his version of events after the assassination of an American President which was praised by critics, but lambasted by journalists.

He is known, more than anything else perhaps, for his trilogy about the Vietnam War. Platoon, the first in the trilogy, won Best Picture and Best Director Oscars; the second, Born on the Fourth of July, won his Best Director, and gave Tom Cruise the best performance in his career. The third, Heaven & Earth, did not do much, but immediately following this trio he made Natural Born Killers, a stark indictment on the American media that is as ruthless as it is wry. He also directed JFK, his version of events after the assassination of an American President which was praised by critics, but lambasted by journalists.

Crucial friendship

Stone has courted considerable controversy since then. This is not really surprising. What is surprising is that he hasn’t relented since. From interviewing Fidel Castro to striking up a crucial friendship with Vladimir Putin, he has shifted to documentaries in recent years. His The Untold History of the United States is as pivotal to revisionist historical scholarship as is Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. Comandante is one of no fewer than three documentaries he made on Castro, the other two being Looking for Fidel and Castro in Winter. Not surprisingly, his sympathies tend to rest with such figures.

It is one of the greatest ironies of Hollywood that its most sincere radicals tend to take part in films that cannot, by any stretch of the imagination, be considered radical. This is as true of Stone as it is of Ridley Scott and Dalton Trumbo. I have mentioned Midnight Express, but a far more peculiar outing for Stone was Conan the Barbarian. Fawned on and admired by the political right, Conan the Barbarian reeks of sort of gung-ho male chauvinism that the man would repudiate in his later work. Conan was, however, not the last work of its kind: in 2002 he was slotted in to direct Mission: Impossible, a movie which projects a narrative of Russian villains that Stone has elsewhere critiqued and lambasted.

Stone’s own upbringing is a case in point. Born to a Frenchwoman and an American stockbroker, he was raised in New York City and grew up in Manhattan and Connecticut. He was admitted to Yale University, but in 1965 to teach English in Saigon, South Vietnam. Two years later he enlisted in the US Army, and for less than a year he served and was twice wounded in action. Three years later he graduated from New York University with a BA in film. His debut, a short film on Vietnam, was well-received. Working as a salesman later, he worked on a couple or so flicks before winning an Oscar for Midnight Express.

Stone’s own upbringing is a case in point. Born to a Frenchwoman and an American stockbroker, he was raised in New York City and grew up in Manhattan and Connecticut. He was admitted to Yale University, but in 1965 to teach English in Saigon, South Vietnam. Two years later he enlisted in the US Army, and for less than a year he served and was twice wounded in action. Three years later he graduated from New York University with a BA in film. His debut, a short film on Vietnam, was well-received. Working as a salesman later, he worked on a couple or so flicks before winning an Oscar for Midnight Express.

[SUBHEAD] Conservative worldview

By the time he made Platoon the political atmosphere in the US had changed considerably. Directors were still making films about American foreign policy, especially in Latin America – Under Fire, featuring Nick Nolte and Gene Hackman, may have been the best of them – but with much less vigour than had been the case in the 1960s and 1970s. Partly, this was owing to the revival of the studio system. Earlier directors had been in control; now studios and big production companies were. While Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland could make F.T.A., a satirical documentary on Vietnam, in 1972, and while Francis Ford Coppola and John Milius could make and write Apocalypse Now in 1979, by the turn of the decade all these directors and auteurs were conforming to a more conservative worldview.

The case of John Milius is particularly interesting. Milius hailed from a deeply conservative background. Yet that did not deter him from contributing to an essentially radical point-of-view in Apocalypse Now. If this seems odd and not a bit off, consider that around the same time Stone was writing the screenplay for Midnight Express, a movie as devoid of sympathy for natives as Milius’s work for Apocalypse Now is full of it. Yet barely five years later, Milius was directing Conan the Barbarian and Red Dawn, the latter perhaps the most hawkish Cold War era objet d’art ever made. Hollywood was shifting to the right.

It is from this perspective that we must look at, and appreciate, Oliver Stone’s films. Platoon didn’t just reinforce the radicalism of 1970s Hollywood, it inscribed a new code for younger radical filmmakers. In 1978 Jon Voight won an Oscar for his depiction of a crippled Vietnam veteran in Coming Home. Ron Kovic, a real-life veteran who turned against the War after returning from the battlefront, had served as an advisor for the film. Stone made him the subject of the second instalment in his Vietnam trilogy, Born on the Fourth of July. Born on the Fourth of July reminds you of Coming Home, but unlike the romantic undertones of the latter, Stone’s film is unflinchingly anti-romantic. After the first half or so is done, we know what Kovic takes time to realise: that there will be no end to his torments.

Though a critical and commercial failure, Heaven & Earth also questions conventional narratives about the Vietnam War. Miss Saigon, a massively popular musical based on the French opera Madame Butterfly, had angered antiwar activists for its romanticised depiction of a love affair between a US Marine sergeant and a Vietnamese girl. Stone presents what is, for me, a counter-view to Miss Saigon’s perspective: the girl in his film is not dependent on the American soldier who takes her away, though she is emotionally attached to him, and in the end, after she is forced to separate from him, she returns home. We realise that there is no victory for anyone here: not the Vietnamese, and certainly not the Americans.

Add new comment