The High Level Road, which connected Colombo to the Kelani Valley, was completed the year Sumitra Peries was born, in 1934. The results were extraordinary. Land prices went up, people began moving in, and marshy, hitherto uninhabitable lands along the route were filled up to make way for palatial houses.

Colombo encountered a pivotal shift: by the time the Road was complete the epicentre of the city had moved from Pettah, Maradana, Kotahena, and Mutwal to a wasteland known as the Maradana cinnamon gardens. With Race Course and Royal College moving to this spot, the elite pounced on it. The transformation was considerable.

Residential bungalows

Not surprisingly the new epicentres of the city reflected ethnic, class, and caste patterns. Vinod Moonesinghe tells me when they were not searching for lands in Colpetty, Cotta, and Cinnamon Gardens, the elite built residential bungalows towards the beach. With the High Level Road complete, there was a land grab in the area from Thummulla and Bambalapitiya on the one hand to Thimbirigasya and Wellawatta on the other.

Havelock Town also became a colonial enclave, and over the years it became a residential area for colonial administrators; the locals lived farther away. After the establishment of the Colombo Municipal Council in 1865 these areas were occupied by colonial bureaucrats, and as such the lanes there were named after them after they had passed on: Elibank Road, Skelton Road, and Layard’s Road, to mention just three.

Sumitra Peries and her husband Lester came to live in one of these lanes, which connected Havelock Town to Bambalapitiya, in 1969. People refer to it as Dickman’s Road even now, of course, though it was renamed Lester James Peries Mawatha when the man regarded as the father of our cinema turned 92. Every time I pass that lane, however, all I can think of is one thing: why did they name it Peiris and not Peries?

Symbolic move

Lester passed away three years ago and Sumitra no longer lives in the street named after her husband. Sometime after his death, she moved to Mirihana. The move was symbolic, in particular because the house she and her husband lived in was more than only a house; it was a cultural epicentre, one which every other artist entered and left. I can think of actors, scriptwriters, editors, and cinematographers who visited that house; I can count the number of those who haven’t on my fingers; and I can think of one or two prominent figures in the industry who, in their early years, spent hours talking with Lester.

But then, whenever someone talks of Lester and pays tribute to him, they miss out on the person who stood by him when he could no longer stand for himself. They forget Sumitra. It’s as though she never lived. Why?

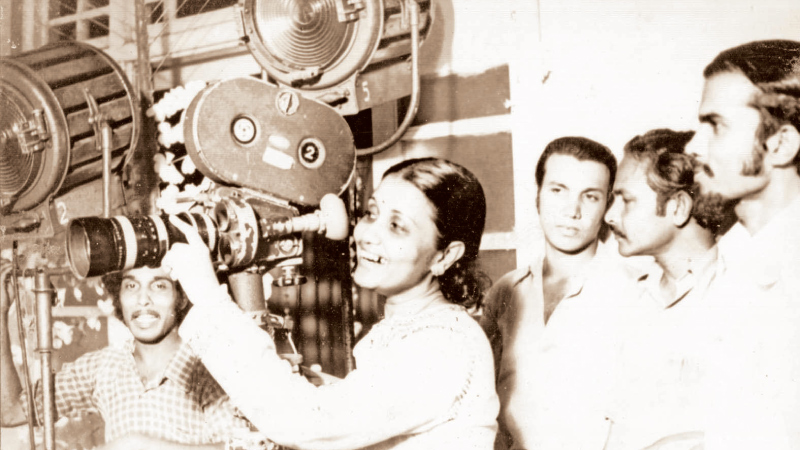

_02112021_SSM_CMY.jpg) All in all, the critical fraternity in Sri Lanka failed to do justice to her and by her. Partly, this has to do with the fact that while Lester rebutted his critics, she never once wrote in reply to them. She was more a filmmaker than a writer, which is saying a lot given that her films reek of a cathartic lyricism that can only be found elsewhere in her husband’s work.

All in all, the critical fraternity in Sri Lanka failed to do justice to her and by her. Partly, this has to do with the fact that while Lester rebutted his critics, she never once wrote in reply to them. She was more a filmmaker than a writer, which is saying a lot given that her films reek of a cathartic lyricism that can only be found elsewhere in her husband’s work.

Suicidal helplessness

When Vasanthi Chathurani breaks down at the end of Gehenu Lamayi, when she commits suicide at the end of Ganga Addara, and when that young boy writes a letter on the sand to his uncle (“to come work for you so that I can help my mother”) in Sagara Jalaya, we stand away, encountering another’s helplessness. We share in her protagonist’s suffering, but we can’t go beyond pity; she brings us closer to yet also distances us from their plight. Some of the most poignant films I’ve seen have this quality, and it is there in her films.

For the critics this was not enough. Ananda Jayaweera in a review called Gehenu Lamayi “an anti-women film to beat them all”, irrelevant considering the films he compared it to: Duhulu Malak (where the wife, having dabbled in infidelity, returns to the husband in the end), Veera Puran Appu (where the wife never takes part in her husband’s actions), and Ahasin Polawata (where the wife puts up with the husband’s fury).

The truth was that there was nothing anti-women about Sumitra’s films; to say otherwise would be to consider some of the most sympathetic portrayals of women in cinematic history as, what else, anti-women.

No mere filmmaker

Sumitra wasn’t just a filmmaker, of course. She led other lives. She was passionate about botany, chess, and the bohemian lives she lived with her brother, Kuru, when the two of them dined and wined in Naples and Malta aboard a 34 foot yacht that anchored off the coast of the French Riviera. Like her father, who had a passion for history, and her brother, who had a passion for prose, Sumitra did her studies in a conventional stream and realised she was not going to follow a conventional career. It was during her stay in the Riviera that, as she once put it for me, “we began to question our purpose in life.”

and Malta aboard a 34 foot yacht that anchored off the coast of the French Riviera. Like her father, who had a passion for history, and her brother, who had a passion for prose, Sumitra did her studies in a conventional stream and realised she was not going to follow a conventional career. It was during her stay in the Riviera that, as she once put it for me, “we began to question our purpose in life.”

She realised her limitations early on. “I didn’t have the discipline to be a writer or poet and I certainly did not have the training to be a historian.” That was when she picked up her first passion, photography. She got so engrossed in it that when she returned to Sri Lanka years later, she would regularly take photographs of her cousins, nephews, and nieces, and cover weddings of relatives with a 16mm Bolex camera.

From there she decided on what path she would take. Soon afterwards she went to Switzerland and enrolled at the University of Lausanne to study French, so that she could “get into a school for photography in France.”

But by the time she was “done with Lausanne”, circumstances had compelled her to take to another path. She found herself in the Ceylon Legation in Paris, where she met Lester and was advised to go study at the London School of Film Technique.

Cinema movement

At London, she remembers, “I picked up everything I could about the cinema and I made friends with many of those who would become the leading figures in the Free Cinema Movement in Britain.” Among these figures was a director who would until his death remain close to her and Lester, Lindsay Anderson.

At London, she remembers, “I picked up everything I could about the cinema and I made friends with many of those who would become the leading figures in the Free Cinema Movement in Britain.” Among these figures was a director who would until his death remain close to her and Lester, Lindsay Anderson.

What happened later, we know: she returned to Sri Lanka, served aboard Lester’s second film, Sandesaya, as its assistant director, and married Lester in 1964.Right after she became the editor of Lester’s first few films, she carved a path as an editor of documentaries. Her first job was a film about fishing, Home from the Sea, which had Gamini Fonseka and Titus Thotawatte’s wife Sujatha as a fishing couple.

It was followed by three other documentaries: FortyLeagues from Paradise (about Sri Lanka, done for the Tourist Board), Too Many Too Soon (about family planning, done with Lester), and a piece on the Kandy Perahera. These were followed in the eighties by a few stints in television, including adaptations of Gehenu Lamayi and Golu Hadawatha, all of which fitted in with her feature films.

None of these works, documentary, feature, silent, or short, bore fruit. She came quite close to a box-office hit with Ganga Addara, but that was produced by someone else. Of the money it earned, she probably got a pittance. She also came surprisingly close to a hit with her debut. In fact the money earned from Gehenu Lamayi was “enough for us to buy a new house”, but the problem was that after the government changed in 1977, “the value of the rupee fell down heavily.” The value of the money they had invested, in other words, was not the value of the money they would recoup.

Film and paint

Another director, facing these circumstances, would have given up. Sumitra didn’t. She went on to make nine more films, not all of which stood up to the standard she tried to reach in her first four films and reached in her fifth, Sagara Jalaya. We are all richer for this, but I wonder every time I pass that street she no longer lives in: did we ever make her feel that we appreciated what she did? Someone told me that we like to draw and film and paint and dance, but we are averse to helping those who draw and film and paint and dance. In that sense, regrettable as it may seem, we are a nation of “ungratefuls.”

Add new comment