You get the most intriguing gifts sometimes. In 2018, a friend ordered for me a copy of Henry Jaglom’s My Lunches with Orson, a riveting account of the relationship between the greatest American director and the only man who tried to do something for him in his last years.

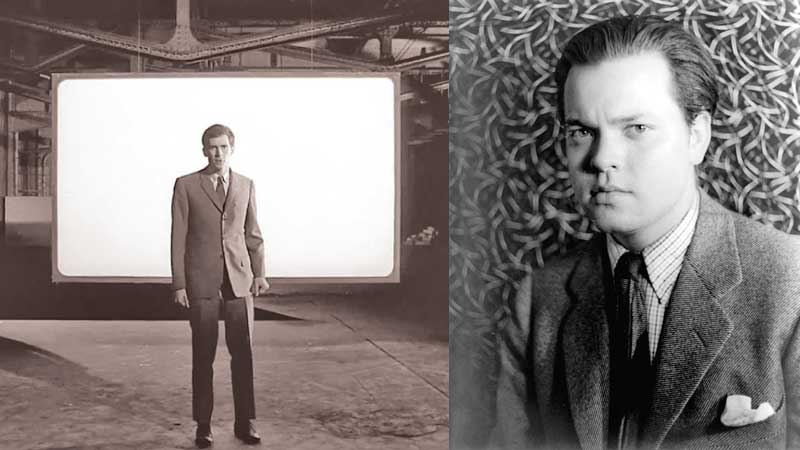

If you haven’t heard the name before, Jaglom was, and is, an independent actor, director, and playwright who has made more than 20 movies; his latest, Train to Zakopane, was released in 2017. While critics have not taken positively to his work, he has come to enjoy something of a reputation today. Jaglom’s first film, A Safe Place, featured Orson Welles as a magician.

The book describes their first encounter: Welles was not willing get involved in debut efforts (“I don’t do scripts by first-time directors”), but as the conversation dragged on, he grew to like this debut and director: give me a cape, he told Jaglom, and I’ll do it.

The book describes their first encounter: Welles was not willing get involved in debut efforts (“I don’t do scripts by first-time directors”), but as the conversation dragged on, he grew to like this debut and director: give me a cape, he told Jaglom, and I’ll do it.

A Safe Place flopped at the box-office, and though it featured the likes of Jack Nicholson, critics despised it: Time Magazine called it “pretentious and confusing.” Jaglom didn’t think too highly of the film himself. Yet if it didn’t score too highly with minority audiences, it brought the young aesthete and his old mentor together: for the rest of their lives, until Welles’s death, the two of them met at a restaurant, Ma Maison, once a week, sometimes twice, to talk over lunch. These meetings began somewhere in 1978 and continued until 1985; except for the final conversation, which Jaglom had to finish in a hurry, they were all tape-recorded.

Peppered descriptions

What did these conversations revolve around? Everything to do with the movies. Welles had a photographic memory, and Jaglom was probably the only one at that point in his life willing to put an ear to it. From the silent era to the 1960s and 1970s, from Eric von Stroheim and D. W. Griffith to his marriages, from his movies to those critics who despised his movies, he dwelt on them all, peppering his descriptions with the most vitriolic adjectives he could think of. Famous for his loud, boisterous candour, he spared no one and did not expect to be spared by anyone. He knew gossip no one else had been privy to until then – like who was aboard the plane with Clark Gable’s wife Carol Lombard when it crashed – and he revealed them all.

At first glance, Orson Welles stands as a “prestige failure”, the epithet critics used to describe our own Lester James Peries. Implicit in this is the assumption that Welles started big and went down: his first attempt, after all, was Citizen Kane, considered the greatest film ever made. The assumption that he deteriorated thereafter draws from critical assessments that place his later work in an unfavourable light. That makes as much sense, however, as judging Lester Peries on the merits of Rekava, or Clint Eastwood on the merits of Play Misty For Me.

At first glance, Orson Welles stands as a “prestige failure”, the epithet critics used to describe our own Lester James Peries. Implicit in this is the assumption that Welles started big and went down: his first attempt, after all, was Citizen Kane, considered the greatest film ever made. The assumption that he deteriorated thereafter draws from critical assessments that place his later work in an unfavourable light. That makes as much sense, however, as judging Lester Peries on the merits of Rekava, or Clint Eastwood on the merits of Play Misty For Me.

One can say critics berated him for not making more Citizen Kanes. What those critics forget or lay aside, however, are the immense difficulties and hardships he had to endure, at the age of 24 no less, when making it. He and his producers came quite close to bankruptcy, since the film failed to recoup its costs and made a loss of more than $150,000. Given that its story had been based on the life of a powerful, controversial, media magnate, moreover, it took no less than a miracle to ensure its exhibition and distribution; at the Oscars, where it was nominated for nine awards, audiences booed every time the host read its name out.

Perennial theme

Welles’s films are profound in that they say a lot with very little. The best example I can point out is not Citizen Kane, but the movie he made after it, The Magnificent Ambersons. It’s about that perennial theme Martin Wickramasinghe and Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa wrote on, the death of the old rich and the rise of a new: the transition from a genteel family to the family of a wealthy industrialist. The poignancy of the human condition, the restlessness that so defines human relationships, the inability to make known one’s feelings overtly, come out well, and in ways you don’t grasp at once. What’s intriguing about Ambersons, and indeed Welles’s greatest works, is not what it says, but how it puts out what it says.

Welles extensively used overlapping dialogues – though such dialogues were in use earlier, as in the screwball comedies of Frank Capra, Howard Hawks, and Ernst Lubitsch – and he gets and forces you to follow every line, every syllable. Sometimes the characters fail to follow or notice what those they are engaging with are saying, so much so that they have to ask him to repeat himself. In Kane, of course, overlapping dialogues – two, three layers of conversation – force us to delve down to the details, to grapple with what we’re seeing and hearing. Welles was adept at getting us to concentrate: he was perhaps the only who could be called a theatrical director, shocking and awing us without distracting from his stories.

His story suggests what life may have been for a great many of us if we could unleash the artist in us. Orson Welles was born in 1915 to an industrialist father and a suffragette mother. Mother and father did not get along, so they split; for the rest of his childhood, Welles, like the hero of Kane, fell into the care of a foster-father, Maurice Bernstein.

His story suggests what life may have been for a great many of us if we could unleash the artist in us. Orson Welles was born in 1915 to an industrialist father and a suffragette mother. Mother and father did not get along, so they split; for the rest of his childhood, Welles, like the hero of Kane, fell into the care of a foster-father, Maurice Bernstein.

At age 16, he asked Bernstein for permission to leave for Ireland, which was granted. In Dublin he made friends with a future collaborator of his; returning home, he found a home in a theatre troupe he founded, the Mercury Players. The studios fell head over heels in love with him: they loved his voice, which they made use of, most memorably in a radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds in October 1938 that sent close to a tenth of the country’s population into a state of mob frenzy. Three years later, having presented three story ideas for RKO Studios, the intrepid director (he had made two short films earlier) got to make the third of them: about the rise and fall of a press tycoon; initially titled The American, it was based on a script by him and Herman Manciewicz (the subject of David Fincher’s Mank). This was Citizen Kane.

Visual magic

It seemed young Welles could do no wrong, but there was little doubt that, after the fracas he encountered over Kane, he could repeat his magic again. The Magnificent Ambersons never got past the studio censors; they mutilated it, substituting a happy ending for what the director had shot. (He was in Brazil at the time, blissfully unaware of what was going on.)

Eerily as it was, this fate visited upon every other film he made thereafter. If he managed to ward off studio pressures, on the other hand he had to stave off budgetary constraints: for want of a proper location, for instance, Welles shot an entire sequence in Othello – the finest adaptation of the text, one of the best of any Shakespeare text – in a Turkish bath.

Predictably, the quality of his films fluctuated – from the disciplined evenness of Citizen Kane and Ambersons to the more upbeat The Lady from Shanghai to the severely disfigured Macbeth and The Stranger – and so did his moods: having made his exit from America in the McCarthy years, he made Europe his home, though he found neither money nor comfort there, and eked out a living in commercials. One remarkable effort, F For Fake, stood out: part-fiction, part-fact, it’s an essay/montage film about a famous art forger. Though a flop, art-house audiences loved it; today it’s ranked as one of his finer efforts, on par with Ambersons and Shanghai.

There were other efforts: an adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial, never properly financed, and a light-hearted take on Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight. Not all these works rose up to the same level as Kane, Ambersons, and Othello: The Stranger overdoes itself after the first hour, Touch of Evil confuses and befuddles, and Macbeth is a Shakespearean mess.

By the time he met Jaglom, the establishment had given up on him; that explains the bitterness with which he views even his friendliest acquaintances throughout his conversations in Jaglom’s book. On October 11, 1985, officials found his body on the floor at his apartment in Las Vegas; having lived his childhood years in the US, and having left it during his formative years, he had returned with the hopes of getting money for further projects.

It was not to be; as Jaglom notes in his epilogue, many of those whom Welles himself had supported or introduced to the industry in some way never came back to help. This, of course, was the fate that befell D. W. Griffith and Eric von Stroheim: the auteurs of the silent era whose link to the sound era comes to us through Welles. Like those two artistes, critics rarely reviewed his work: “They don’t review my work,” Welles once complained.”[T]hey review me.’’ And in the end, that’s what they talked about: not the movies, but the man who made them.