I am a writer and to a certain extent I feel I understand what I do. At least, I know I try to work hard at my job. And sometimes I get things right, and sometimes I don’t. But when it comes to book dedications, I can never figure out if I did the right thing or not; looking back now, some of the dedications I wrote for my books seem too mild or two wild.

But of course, not as wild as Lemony Snicket’s dedication in ‘A Series of Unfortunate Events,’ “To Beatrice–darling, dearest, dead.”

Nor are they as funny as what Nelson Demille wrote in ‘Wild Fire’: “…There is a new trend among authors to thank every famous person for inspiration, non-existent assistance, and/or some casual reference to the author’s work. Authors do this to pump themselves up. So, on the off chance that this is helpful, I wish to thank the following people: the Emperor of Japan and the Queen of England for promoting literacy; William S. Cohen, former secretary of defense, for dropping me a note saying he liked my books, as did his boss, Bill Clinton; Bruce Willis, who called me one day and said, “Hey, you’re a good writer”; Albert Einstein, who inspired me to write about nuclear weapons; General George Armstrong Custer, whose brashness at the Little Bighorn taught me a lesson on judgment; Mikhail Gorbachev, whose courageous actions indirectly led to my books being translated into Russian; Don DeLillo and Joan Didion, whose books are always before and after mine on bookshelves, and whose names always appear before and after mine in almanacs and many lists of American writers—thanks for being there, guys; Julius Caesar, for showing the world that illiterate barbarians can be beaten; Paris Hilton, whose family hotel chain carries my books in their gift shops; and last but not least, Albert II, King of the Belgians, who once waved to me in Brussels as the Royal Procession moved from the Palace to the Parliament Building, screwing up traffic for half an hour, thereby forcing me to kill time by thinking of a great plot to dethrone the King of the Belgians. There are many more people I could thank, but time, space, and modesty compel me to stop here.”

Not all dedications are as long as Demille’s. Charlotte Brontë signed ‘Jane Eyre’ off to Thackeray, plain and simple, while Anne was even sparer, offering no dedication at all in ‘Agnes Gray.’ This would have been because the sisters needed to conceal their identity, which in turn meant keeping their dedications a secret too. Of course, other writers, mostly men of letters like Wilkie Collins, could confidently dedicate their books to whoever they liked. Thus Collins dedicated ‘The Woman in White’ to “Bryan Walter Procter – from one of his younger brethren in literature who sincerely values his friendship and who gratefully remembers many happy hours spent in his house.” While Collins’s friend Dickens wrote in the ‘Bleak House’ his book is “Dedicated, as a remembrance of our friendly union, to my companions in the guild of literature and art.”

As writer Henriette Lazaridis points out these dedications were written with ulterior motives. “There’s nothing plain and simple about even the most seemingly simple dedication,” says Lazaridis. “Collins’s to Procter can be seen as a strategic move to ally himself with someone whose name hardly made it to posterity but who, at the time, held some reputation in Collins’s world. And Brontë’s nod to Thackeray may have been purely reverential but looked to contemporary readers like proof of a romantic connection.”

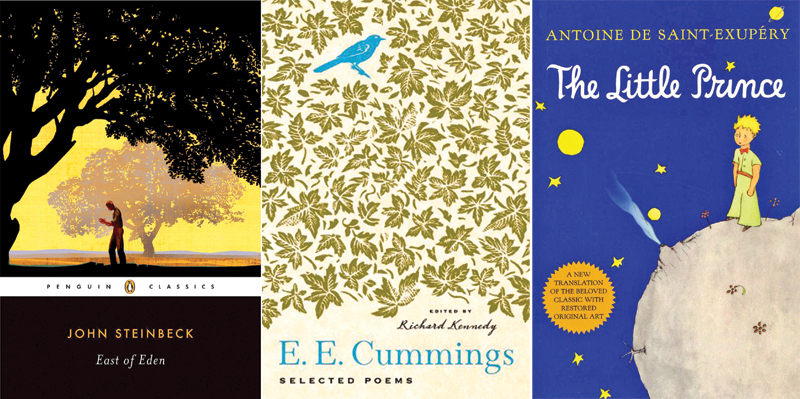

There are also dedications that are sheer art. You will find a beautiful and heartbreaking one in Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s “The Little Prince.” The book was published during World War II, and Saint-Exupery dedicated the book to a friend living in occupied France at that time: TO LEON WERTH. I ask children to forgive me for dedicating this book to a grown-up. I have a serious excuse: this grown-up is the best friend I have in the world. I have another excuse: this grown-up can understand everything, even books for children. I have a third excuse: he lives in France where he is hungry and cold. He needs to be comforted. If all these excuses are not enough, then I want to dedicate this book to the child whom this grown-up once was. All grown-ups were children first. (But few of them remember it.) So I correct my dedication:TO LEON WERTH. WHEN HE WAS A LITTLE BOY.”

Some book dedications are straightforward. (Mark Twain dedicated “Tom Sawyer” to his wife, with affection.) Some are mysterious. (“Peyton Place” was dedicated “To George, for all the reasons he knows so well.”)

As an undergraduate, I remember pausing to appreciate the dedication to T.S Eliot’s ‘The Wasteland”. I had grabbed the book, off the library shelf, and was enticed by the dedication; ‘For Ezra Pound; il miglior fabbro.’

I was baffled at first, but later discovered that the dedication is drawn from The Divine Comedy, the 14th century epic poem by Dante. ‘The Divine Comedy’ is divided into three parts — Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso — describing Dante’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and finally Paradise. Eliot returns to this poem throughout ‘The Waste Land’ and in the dedication refers to Canto 26 of the Purgatorio where Dante writes of the poet Arnault Daniel. In ‘The Waste Land,’ Eliot passes the compliment on to Pound, who helped edit The Waste Land by calling him ‘il miglior fabbro’ the better craftsman. Since then, I have often addressed my fellow writers with the same words acknowledging their greatness over mine.

Yet, it was only when I started to publish my own work that I realized the importance of the dedication page. As Sloane Tanen writes, “A book dedication is a proclamation, right up front, with which an author can honor a person, a small group of people, even a thing.”

Once you begin to pay attention to dedications, you will find books dedicated to caffeine, dogs, alcohol, even pizza. And there are even hostile dedications. Perhaps the most well known of this variety is e. e. cummings in his collection No Thanks. Having published his poems with the money his mother gave him, he lists the fourteen publishers who rejected his work in the shape of a funeral urn.

While it is important not to overthink the dedication, a writer must remember that essentially everyone who reads your book will see it. Under the best circumstances, the dedication page will create a small intimacy between the author and the reader. Under the worst circumstances, it will offend someone, perhaps the people to whom the book is not dedicated and think it should be. Most likely, few will really care.

Experts say, ideally, your dedication should match the tone of your book. Carl Sagan nailed this in his dedication for Cosmos: “In the vastness of space and immensity of time, it is my joy to spend a planet and an epoch with Annie.” Jack Kerouac also got this right in Visions of Cody: “Dedicated to America, whatever that is.” We can glean a lot from both of these dedications. Carl loves Annie (his wife) as much as he loves space. Kerouac, on the other hand, hates America as much as he loves America. Likewise, Shannon Hale’s dedication for Austenland is very funny, like the novel: “For Colin Firth: You’re really a great guy, but I’m married, so I think we should just be friends.”

Emily Ludolph describes a dedication as “A secret message hidden in plain sight.” Ludolph sees the dedication functioning almost as a two-way mirror. The reader can only perceive a certain amount of the true story. “There’s a layer of decoding … Sometimes, you understand the book better if you understand who it comes from and who it’s for,” she says.

Of course, the most common sort of dedication is to one’s family or a loved one. Unless you change partners regularly, in which case, “the love of my life,” might be best. Daughters and sons are natural subjects. P. G. Wodehouse gave Heart of a Goof: “To my daughter Leonora without whose never-failing sympathy and encouragement this book would have been finished in half the time.”

As for me, so far, I have dedicated all my books to the wind, the trees, the yellowbutterflies and my readers.

But experts on the topic don’t recommend this type of dedication. They say you should dedicate your books to your readers only if you are Mark Twain. They argue such a dedication assumes that you have readers, but what if you have none.

Oh, well.