Words can be very visual. And pictures can speak. Good words and good art, that is. Art forms can communicate with one another and they communicate artist and art to us.

Now there is text and there is subtext. It’s the same with a photograph. There’s the obvious and the subtle, things we ‘get’ immediately and things that we could miss. A text can speak to us differently at different times. It’s the same with photographs, sculptures, music, dance, theatre, films etc.

What this means is that there are layers of meaning embedded in art. The ‘reader’ can always misread and this is why in a sense a work of art belongs as much to the artist as to those who ‘receive’ it.

So there’s poetry in photographs and the ‘reader’ obtains it in the language of his/her persuasions, be it cultural, political, life-experience or some mix of these. What’s ‘apparent’ is not necessarily what is there. There are backstories that don’t get captioned or indeed cannot be framed.

So there’s poetry in photographs and the ‘reader’ obtains it in the language of his/her persuasions, be it cultural, political, life-experience or some mix of these. What’s ‘apparent’ is not necessarily what is there. There are backstories that don’t get captioned or indeed cannot be framed.

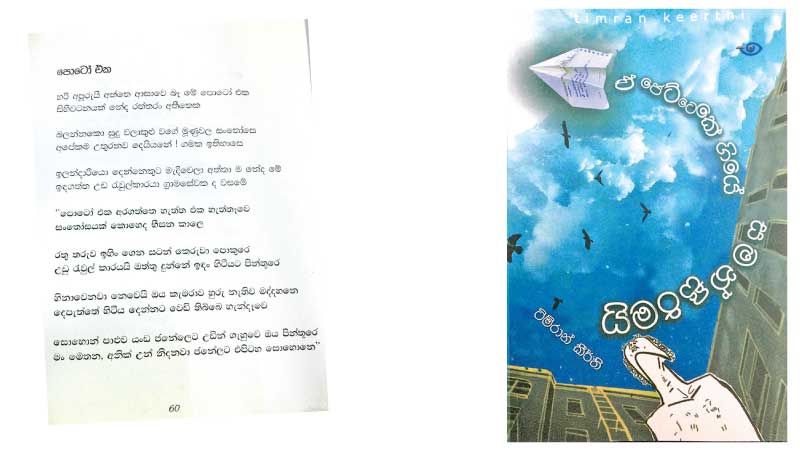

Timran Keerthi, award-winning poet, relates a story that sheds light not on just a single photograph but on ‘seeing’ and ‘seeing beyond’ in a poem aptly titled ‘Poto Eka (The Photo).’

The Photo

It’s amazing grandpa, this photo mesmerizes a memento of a precious past is it not?

Look at the faces alight with joy like the whitest clouds there’s something quintessentially ours that overflows, the history no less of the village, dear god!

is it not you, grandpa, flanked by those two young men and the mustached man seated there, the headman?

‘The photo was taken in seventy or seventy-one in a time of terror, what talk of joy?

with the red star as guide we fought as one pack the mustached man, although seated here, that ratted in the midday sun unused to the camera we weren’t smiling

It was in the evening that the two on either side were shot to dispel the cemetery’s gloom, the photo above the window I placed

everyone’s asleep in the cemetery beyond the window, but I am here .’

Where have they gone, those who smiled at a photographer? Were they real, the expressions, or else art-directed or simply a convenient disguise? What was said by he who stood in the corner? Was anyone listening?

How do we tease out stories from pictures? What if Timran wasn’t listening? What if the grandfather chose not to speak?

It’s not something limited to photographs and the arts in general. If we look around we see faces. We see expressions. We hear words. There are gestures. A lot is said and we may or may not hear, but how about that which remains unsaid, that which is hidden by smile or silence or words chosen so as to distract and divert?

There’s small print and footnotes. There are endnotes no one bothers to read. There’s a glossary glossed over. There are narratives meant to be read and there’s text deliberately held back.

The stories of the defeated often are buried with them. This is the truth about 1971. It is true for that other and far more brutal bheeshanaya towards the end of the 1980s. It is true about the thirty-year long conflict between security forces and the LTTE, of course with the Indian Peace Keeping Force and other armed groups such as the EPRLF playing not-so minor roles.

There are terrible moments that have nothing to do with conflicts such as these. There’s a story in a factory, a university, a corporate board room, a security post, a prison and a military camp. There’s one that’s written along a dirt track in the Dry Zone and another that is cut by barbed wire. There’s poetry that spills on the boots of laborers laying a highway. There are innumerable paintings of various kinds of violence. Unfinished.

Timran noticed. And we cannot see portraits and group photos the way we did before. The eyes just won’t move fast.