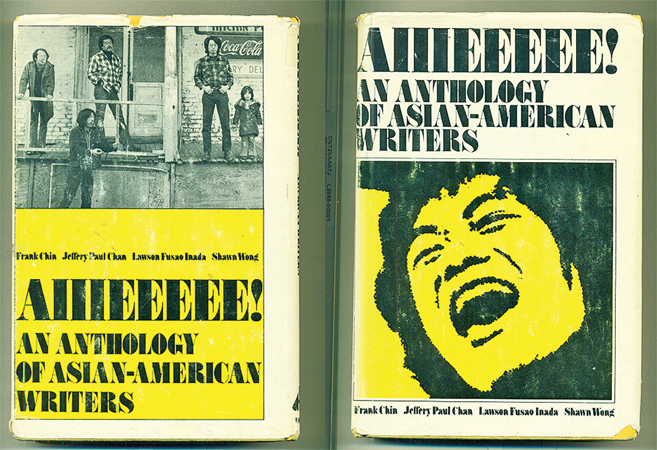

I initially encountered Aiiieeeee! in the winter of 2003, during my first Asian American literature course at Wesleyan University. My professor deftly outlined the major critiques that had been leveled against the anthology over the years-the narrowness of its definition of Asian America, its overtly masculine tone and underrepresentation of women, its American-born, monolingual perspective-and with each contention, I grew more indignant.

The magnitude of my indignation was perhaps out of proportion with the size of its source, based as it was on my thin reading of a thin selection: no more than the twelve pages that made up the original 1974 preface. We did not read the introduction that followed, nor the selections that constituted the bulk of the anthology (although we did read two of the excerpted novels, America Is in the Heart and No-No Boy, in their entirety).

I am ashamed to admit that not until recently did I actually read the entire anthology, cover to cover. Yet I would venture that this oversight is not uncommon among Asian Americanists of my generation. Indeed, if what defined Asian Americans for the editors of Aiiieeeee! was that they “got their China and Japan off the radio, off the silver screen, from television, out of comic books,” then for years perhaps what defined me as an Asian Americanist was where I didn’t get my Asian America: which is to say, from Aiiieeeee!

Earliest days

In short, students of Asian American literature have often been far more familiar with what is wrong with Aiiieeeee! than with Aiiieeeee! itself. From the earliest days of its publication, many Asian Americans did not hear themselves in the scream of Aiiieeeee!, did not see themselves in the “our” of its “fifty years of our whole voice.” They chafed against what they saw as the editorial limiting of “authentic” Asian Americanness to “Filipino, Chinese, and Japanese Americans, American born and raised.”

This act of border drawing, by excluding Pacific Islander, Korean, and South Asian Americans (among others), further contributed to critics’ rejection of Aiiieeeee!’s brand of Asian American cultural nationalism as more divisive than unifying.

Add to that the damning charge of gender bias. Many, including the editors themselves, have interpreted this critique to mean that women writers were underrepresented in, even actively excluded from, the anthology. In truth, writing by women made up nearly 30 percent of the literary selections. But the real criticism wasn’t so much about the statistical representation of female bodies in the literature of Asian America gathered here; it was about the perceived erasure of female voices in the theory of Asian American writing that Aiiieeeee! delineated in its original preface and introduction.

In an aggressive and largely denigrating way, the editors invoked-but did not anthologize-Asian American women writers like Jade Snow Wong, Monica Sone, Sui Sin Far, Betty Lee Sung, and Virginia Lee. Not that women were the only ones to suffer the editors’ wrath-the Chinese American author Pardee Lowe, in particular, was alternately razed and raised up as a straw man pandering to white American readers’ appetite for “actively inoffensive” stories of exotic Orientalia. But it was, statistically speaking, mostly women who were criticized for their presumed assimilationist ideals.

Numerical representation

The reason for omitting the gendered targeting of this critique, according to the editors themselves, was simply numerical fact: there were at the time far more published female Asian American writers than male. The problem with the imbalance, however, went beyond numerical representation. Feminist critics lambasted Aiiieeeee! for its conceptual phallocentrism: the way it took the “sensibility” of the Asian American man as a metonym for Asian Americanness as a whole.

The editors, in other words, too quickly subsumed the experience of Asian American women under a default ethnic humanity. In the same problematic way that the word man has historically been used in English as a synonym for all human beings, the editors declared that “a man in any culture speaks for himself. Without a language of his own, he no longer is a man” and that “the white stereotype of the acceptable and unacceptable Asian is utterly without manhood … contemptible because he is womanly, effeminate.”

Attempting to spring the trap of “racist love” (Frank Chin and Jeffery Paul Chan’s term for white America’s embrace of Asians as a model minority), the editors risked falling into the trap of misogyny.

- Paris Review

Add new comment