India’s new port-led development strategy, Sagarmala, is an ambitious, large scale project that is slated to improve India’s port operational efficiency and harness the potential of India’s long coastline. This Policy Brief looks at Sagarmala and its implications for Sri Lanka, and recommends steps to be taken in order to secure the opportunities that could arise from this initiative.

I. Introduction

Maritime trade plays an important role in the Indian Ocean. In fact, one-third of global bulk shipping trade,1 which includes petroleum products and coal, transits through this region. The maritime sector makes a significant contribution to the economy of many countries in that region. However in India, due to infrastructural constraints and poor operational performance,2 the growth of the sector has slowed in recent years. To address this, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi rolled out the ambitious Sagarmala3 development project in 2015 to boost India’s maritime sector. This port-led development strategy is designed to address some of the most pressing issues faced by Indian ports and improve its operational efficiency. At the same time, this is likely to have major implications for shipping sectors across the region, including Sri Lanka. Arguably, the development of these ports could lead to increased competition between India and Sri Lanka. However, this article discusses that while Sagarmala may well be a threat and lead to increased competition in the region, there is also a possibility that it could pose as an opportunity for Sri Lanka, especially for the Port of Colombo. This policy brief will explore the current state of ports in India and Sri Lanka, introduce Sagarmala and review some challenges and opportunities and finally provide some policy recommendations.

II. Comparison of Indian and Sri Lankan Ports

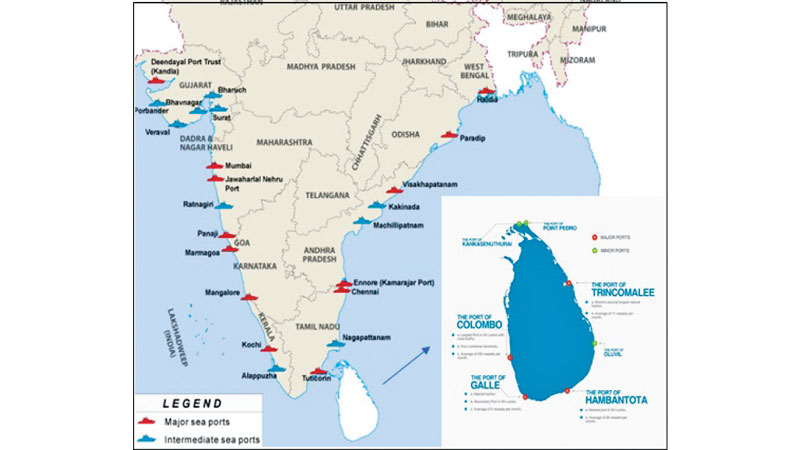

Both India and Sri Lanka, are key players in maritime trade in the South Asian region (defined as Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Maldives and Sri Lanka), with India being the biggest player holding the lion’s share of 53% of the regional market in terms of container throughput followed by Sri Lanka holding 24% and Pakistan and Bangladesh holding 12% and 10% respectively in 2017. Both nations have several key seaports which sit near the globally important, East-West shipping route. Given these locational advantages, within South Asia, Indian and Sri Lankan container throughput has been growing faster than the regional average of 7.25% with 9.71% and 8.71% (2017) respectively.

There are four major ports in Sri Lanka including Colombo Port, Galle Port, Hambantota Port, and Trincomalee Port. Colombo Port is by far the largest, dealing with 94.84% of total handled cargo in the country in 2017. With three operational terminals,4 Colombo has a collective installed capacity of about 7.1 million5 TEUs (Twenty-Foot Equivalent Units) and handled roughly 6 million TEUs in 2017 and recently crossed 7 million TEUs in December 2018.6

Between 2014 and 2017, container throughput at Colombo port grew at an average rate of 9.8% as shown in Figure 1. Interestingly, growth peaked after Colombo International Container Terminal (CICT) operations commenced in 2013. This was mainly because the port was able to facilitate more shipments and larger vessels as CICT is the only deep-water terminal in South Asia capable of handling the largest vessels afloat.

The ports overall performance compares well with the South Asian regional averages and other Indian Ports. In a comprehensive study by the World Bank,7 it was found that, the number of days it takes a ship to dock or the “Waiting Time” at Colombo Port was only 0.09 days, which was far quicker than the South Asian average of 2.08 days (MRE). In addition, the percentage of idle time at berth was roughly 6.9%, in Colombo but 19% within the region. Port efficiency, among other factors have facilitated growth in throughput over the years.

On the other hand, India has 12 major ports out of which Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust (JNPT) in Mumbai and Chennai Port handled 18% of total Indian cargo in 2017. Both these ports have a locational advantage, as they are situated on either side of the East-West shipping route. Collectively, they have an installed capacity of roughly 7.3 million TEUs and handled about 6 million TEUs in 2017.

One of the five terminals at JNPT, the Bharat Mumbai Container Terminal operationalised in 2016 and thus JNPT was able to boost its port throughput growth from -6% to 14.6%8(YoY) in 2017. Similarly, Chennai port throughput growth contracted by -5% in 2016, but grew at a rate of 4.5%9(YoY) in 2017. However, under the Sagarmala initiative, both ports have been identified for further expansion, due to capacity constraints weighing heavy against growing demand.

As for port performance, both Indian ports have various strengths, and have been improving over the years. Idle Time as a share of total time at berth reduced significantly at JNPT from 36% in 2000 to 8.1 % in 2012. Similarly, in the Chennai port, it reduced from 25% to 14.7% (MRE) respectively. However, in terms of Waiting Time, the Chennai port was able to reduce it by 73% over the 12-year period (2000-2012) to 0.35 days, while Waiting Time at JNP has been slightly worsening. These ports perform reasonably well compared to the regional averages, but not across all indicators.

On an aggregate level, the average growth rate of container traffic in India fell from 15.5% between 2001 and 2008 to 7.2% between 2010 and 2014 as shown in Figure 2. There are many factors that could have contributed to this downturn, including slowing world trade growth in the post-crisis period. Within the domestic framework, one could also argue, that Indian ports lacked the capacity to facilitate further shipments due to various infrastructural constraints and poor operational performance10. In a bid to address these issues, the Sagarmala initiative was introduced.

III. Is Sagarmala a Threat?

The Sagarmala initiative is based on four components, namely; Port Modernization, Port Connectivity, Port-linked Industrialisation, and Coastal Community Development. Sagarmala expects to invest over INR 8 trillion11 (about USD 50 billion) to further develop this infrastructure with 577 projects having been identified so far, and 49212 already at various stages of implementation. Some of these projects are designed to increase the capacity of the 12 major ports by 62% to 1,414.5 million tonnes per annum (MTPA).13

This project mainly attempts to address a number of issues that have restricted the growth of the Indian shipping sector, especially that of inadequate infrastructure. Port capacity limitations in India have so far resulted in major shipping lines turning to other ports in the region, including the Port of Colombo. In 2017/2018, Colombo attributed 42%14 of its traffic to transshipment of Indian cargo.

However, this could change in the coming years as Indian port capacity begins to expand under Sagarmala. For example, the Enayam Port in Tamil Nadu, which is only 10 nautical miles from the international East-West shipping route, could have its capacity increased from 10 to 18 million TEUs;15 by comparison, Colombo’s installed capacity is currently 7.1 million TEUs.16 Meanwhile, Vizhinjam Port in Kerala is being designed to be the world’s deepest multipurpose seaport17 Vizhinjam has an 18-20 metre natural draft depth;18 this is already greater than Colombo, which only has a depth of 18 metres.19

The recent relaxation of the cabotage rule in India20 is also likely to adversely impact21 Sri Lanka’s transshipment trade in the short to medium term. As foreign flagged vessels will now be allowed to transport goods from one Indian port to another, Sri Lanka’s ports might no longer play a major role in transshipping these goods. This could be a major blow as the Sri Lankan shipping industry relies heavily on its transshipment role. As such, both port expansions under Sagarmala as well as the liberalisation of Indian shipping regulations could deteriorate the feeder network that Sri Lanka has been able to maintain, thereby undermining its competitiveness as a hub.

IV. Is infrastructure expansion enough?

However, one could argue that infrastructure expansion alone won’t make Indian ports more competitive, and that if one adopted a more holistic view of port performance, Colombo could still retain its market share. Shipping lines often place great value on port efficiency, as it translates to lower costs. In this respect, Colombo is generally more efficient than Indian ports. On average, selected major Indian ports have a Turn Around Time (TAT)22 of 2.16 days, which is far longer than Colombo’s average of 0.86 days (MRE). Colombo also has a less complex administrative process compared to Indian ports. Currently, Indian ports require 10 forms and 22 signatures on average for administration purposes, whereas Colombo Port only requires 7 and 13 respectively.23 As a result, border compliance24 in India takes roughly 9 more days, compared to Sri Lanka.25

While India has a higher overall ranking of 77 in the Doing Business Report 2018,26 they perform relatively poorly on some sub-indices, one such area being average trading costs. The average cost to export and import goods (which includes documentary and border compliance costs) from Sri Lanka is USD 424 and USD 583 respectively, whereas in India, the costs are higher, being USD 474 and USD 678 respectively. To add to this, the investment environment in Sri Lanka also compares well against India. According to the “Starting a Business” sub-index, it takes only 9 days to open a business in Sri Lanka, whereas in India, it takes roughly 30 days. Due to the low-cost advantage and the deregulated registration process, one could argue that Sri Lanka generally has a more conducive business environment than India.

As the overall trading environment in Colombo is generally more welcoming, there is potential for the Port of Colombo to grow as the region’s main transshipment hub, ahead of Indian ports, even when the latter have had its infrastructure upgraded under Sagarmala.

V. Is Sagarmala an Opportunity?

India is currently the world’s fastest-growing economy27 and is likely to account for 9.5% of World GDP (PPP terms) by 2025 according to a study by the Overseas Development Institute.28 Meanwhile, Sri Lanka is relatively a much smaller economy, and while it is growing above the world average, it is likely to only account for 0.2% of World GDP by 2025. As India gears up to meet growing demand, certain opportunities may become available for Sri Lanka which could catalyse its growth and accelerate the rate of development.

Besides the possibility that Sagarmala’s infrastructure-led development alone, would not result in undermining Colombo’s regional hub status, there is also the possibility that the project may create positive spillovers for the region, resulting in a win-win outcome for both Colombo and Indian ports. For example, with India’s ability to accommodate greater cargo volumes as a result of Sagarmala would arguably lead to an absolute increase in regional container traffic. Over the years, the shipping environment has gravitated towards a hub and spoke distribution system.29 This is where large vessels load more cargo and ship it to one hub or distribution centre. These centres receive products from various origins, which they then consolidate and ship off to their final destinations through feeder vessels. As a result of this trend, higher traffic volumes could drive down the cost per TEU handled for both shippers and shipping lines,30 drawing further shipping lines to the region to benefit from scale economies. Given that the Port of Colombo was ranked 13th in the Drewry Global Container Port Connectivity Index31(4Q 2017) and is the only South Asian port to be listed in the top 20 on this index, its existing complex networks are likely to strengthen and grow under this expansion of container traffic. Therefore, with this influx of container traffic, Sri Lanka may be in a better position to strengthen as a transshipment hub. As such, Sagarmala could create something of a complementarity effect between the ports of the two countries.

VI. Policy Recommendations

In the long run, securing a complementary relationship with Indian ports will, to some extent allow Colombo to maintain its competitiveness as the region’s transshipment hub. Sri Lanka should work toward (i) strengthening its links across different maritime networks and (ii) investing in expanding capacity and (iii) providing more complimentary services, that are aligned with the nation’s goal of becoming a regional hub.

Connectivity

One such way of improving maritime network connectivity is through leveraging regional and bilateral coastal agreements, such as the bilateral coastal shipping agreement32 with Bangladesh. This agreement is designed to give third-party access for Sri Lankan vessels to East Indian Ports. It is expected that it will improve transit time, reduce costs and improve connectivity between Bangladesh’s Chittagong Port and Colombo. Similarly, Sri Lanka could also look to regional platforms to further develop its network. Currently, a coastal shipping agreement33 is being drafted under the BIMSTEC framework, which is designed to promote greater and more cost-effective movement of cargo. By leveraging these agreements, Colombo would be able to expand its feeder network to facilitate the existing hub and spoke system and strengthen as a regional transshipment hub.

Capacity

Recently a tripartite agreement between the three terminals was signed in order to ensure smooth port operation and significantly reduce waiting time. Though this will help in the short term, Colombo port is likely to reach its full capacity quite soon. One way to resolve this issue is to prioritise the construction of the East Terminal, Sri Lanka’s second deep draft terminal34 after CICT. Once completed, it will be instrumental in reducing shipping congestion and will allow Colombo port to maintain its upward growth trend, adding 2.4 million TEUs35 in capacity. In addition, investing in infrastructure and equipment should be prioritised to ensure that demand is being matched with efficiency and good service. As such, reforms should not delay, and proactive measures must be taken in order to overcome this bottleneck.

Services

Similarly, Sri Lanka could also work towards adopting modern distribution services and warehousing in order to secure clients in this competitive market. Currently, there are talks of encouraging Multi-Country Consolidation (MCC) services,36 where half-full container loads are brought to Sri Lanka and cargo is reshuffled into full container loads and shipped to the destination country. These types of logistics services would complement Sri Lanka’s vision of becoming a stronger transshipment hub and would help it fully exploit the scale economics opportunity offered by Sagarmala.

VII. Conclusion

Sagarmala’s infrastructure-led development strategy and the repeal of the cabotage law are likely to boost India’s maritime sector by a large scale. Though this might mean increased competition within the region, especially for Colombo, one could argue that infrastructure development alone won’t be enough to capture more market share. Especially when Colombo performs better in terms of port operational efficiency than most Indian ports. However, Colombo should take advantage of the scale economics Sagarmala could offer and leverage regional agreements to further strengthen as a transshipment hub. India’s progression is inevitable but by being proactive, Colombo may be able to retain its market share and hold a temporary advantage.

Nevertheless, Sri Lanka should not rest on her laurels. In order to remain competitive, Sri Lanka should strengthen its national port development strategy and address bottlenecks that constrain the shipping and port industry. Increasing capacity through reviving the East Terminal37 at the Colombo Port and investing in infrastructure and other ancillary services would allow further growth.

Implementing forward-looking policy would enable Colombo to be better able to accommodate future demand and be better equipped to indirectly benefit from initiatives such as Sagarmala.

(Written by Pabasara Kannangara, from Lakshman Kadirigamar Institute)

Add new comment