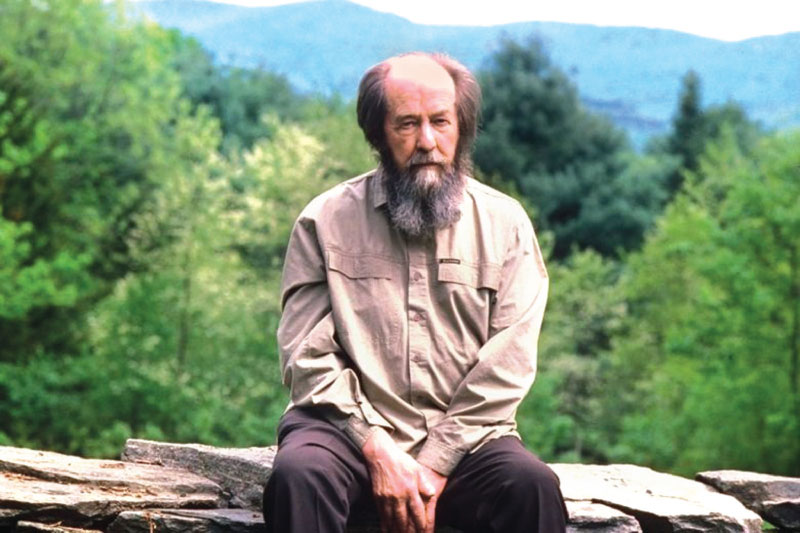

One hundred years ago this month, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was born in Kislovodsk (“acidic waters”), a curative town in the North Caucasian foothills of Russia, which was then wracked by civil war. Earlier that year, 300 miles north at Novocherkassk, the capital of the Don Cossacks, former tsarist officers had proclaimed the formation of a Volunteer Army to reverse the Bolshevik coup of 1917. The force, labelled Whites, would go down in defeat, its survivors compelled to disperse into emigration. But Solzhenitsyn – even though he, too, would be forced from his homeland – subsequently won the White movement’s fight with his pen. His novels One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, In the First Circle and Cancer Ward, as well as his nonpareil three-volume literary investigation The Gulag Archipelago, persuasively blackened the Soviet regime at its roots.

One hundred years ago this month, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was born in Kislovodsk (“acidic waters”), a curative town in the North Caucasian foothills of Russia, which was then wracked by civil war. Earlier that year, 300 miles north at Novocherkassk, the capital of the Don Cossacks, former tsarist officers had proclaimed the formation of a Volunteer Army to reverse the Bolshevik coup of 1917. The force, labelled Whites, would go down in defeat, its survivors compelled to disperse into emigration. But Solzhenitsyn – even though he, too, would be forced from his homeland – subsequently won the White movement’s fight with his pen. His novels One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, In the First Circle and Cancer Ward, as well as his nonpareil three-volume literary investigation The Gulag Archipelago, persuasively blackened the Soviet regime at its roots.

According to an estimate by Publishers Weekly, by 1976 Solzhenitsyn had sold 30 million copies of his books in some thirty languages, with sales of the first volume of The Gulag Archipelago accounting for up to a third of that total. Long after Soviet communism came crashing down in 1991, his evocative works based on a multitude of first-hand experiences of the forced labour camp system retain their potency and urgency. If, as the scholar John B. Dunlop has written, “it is as an artist that Solzhenitsyn will be remembered or forgotten”, then he is destined to endure.

Literary cycle

Having earned global acclaim – including the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970, awarded “for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature” – Solzhenitsyn dedicated himself to a literary cycle, The Red Wheel, on Russia’s Revolution. Published in Russian between 1971 and 1991, the series derives its name from a detached carriage wheel that revolves in flames in August 1914, the first of four “nodes” through which the author organized these novels of real and invented personages. That intial instalment appeared in English translation in 1972; November 1916, originally in two volumes, followed in 1985, along with a reworked two-volume version of its predecessor. March 1917, in four books, is only now beginning to appear in English, courtesy of University of Notre Dame Press. (April 1917, in two books, awaits.) In the first volume of March 1917, well translated by Marian Schwartz, many haunting passages can be found, such as Nicholas II’s confrontation with the icon of Christ following his tormented abdication. Still, the overall four-node roman-fleuve runs to nearly 6,000 pages, in ten volumes, deluging readers.

Solzhenitsyn’s history in March 1917, like The Red Wheel as a whole, is refreshingly contingent and a product mostly of human not impersonal forces: the opposite of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, to say nothing of the Marxist structuralism with which Solzhenitsyn originally conceived the work as a youth in the 1930s. True, he does seem to yield to a kind of Tocquevillean resignation at a relentless progression of democracy in the world. But he suggests that Russia would have been best served by elected local self-government, if combined with election-less central rule in the service of the nation, which in his view was (and remained) possible. Instead, The Red Wheel depicts Russia as having been betrayed twice, by an indolent and corrupt homegrown elite, and by a hyperactive and destructive intelligentsia obsessed with implanting “foreign” ideas, which the author portrays as a liberal-socialist continuum. The Revolution becomes something alien. Concepts of foreign or alien, it must be said, present insurmountable difficulties for anyone who would write the history of Imperial Russia and the Revolution. Solzhenitsyn, donning the mantle of Russian nationalist, was a part ethnic Ukrainian who spoke Russian with a Ukrainian accent. His lodestar, tsarist prime minister Pyotr Stolypin, broke his political neck against the stubborn realities of Russia’s heterodoxy even before a terrorist killed off his yeoman efforts at modernization and regime stabilization in 1911.

Gulag Archipelago

The Red Wheel has attracted nothing like the readership of The Gulag Archipelago, the greatest book about, but also of, the Soviet Union. To attempt the work was a crime. Solzhenitsyn wrote it conspiratorially, in fragments, hiding his completed sections in the homes of trusted allies so as not to risk confiscation in one fell swoop by the KGB. He marvelled that he never had the whole work “on the same desk at the same time!” The accumulated pieces, numbering more than 1,800 book pages, twice as long as the Iliad and the Odyssey combined, share a common sensibility, but most stand on their own, like a short story collection. In September 1973, after he had the full manuscript smuggled out to the West on microfilm for translation and publication abroad, the KGB obtained a copy of the whole from his clandestine secretary (Elizaveta Voronyanskaya, who then took her own life).

The police operatives prepared an excellent summary for high officials, capturing most of the author’s central points: the mass arrests and vast prisons camps were the system’s essence, not an aberration; the Gulag gave birth to a distinctive “nation” of prisoners with their own psychological traits, mentality and language; the secret police (NKVD “bluecaps”), too, constituted a recognizable social type. But the work’s crowning theme of suffering as a path to redemption, purification and triumph eluded the KGB analysts – and not them alone – unfolding as it does within Solzhenitsyn’s summons to national repentance and renewed spiritualism. The abridged Gulag Archipelago 1918–56: An experiment in literary investigation, now reissued by Vintage Classics in Thomas P. Whitney and Harry Willetts’s functional translation, might not satisfy devotees of the three-volume monument, but it does attain its aim of readability. - Times Literary Supplement

Add new comment