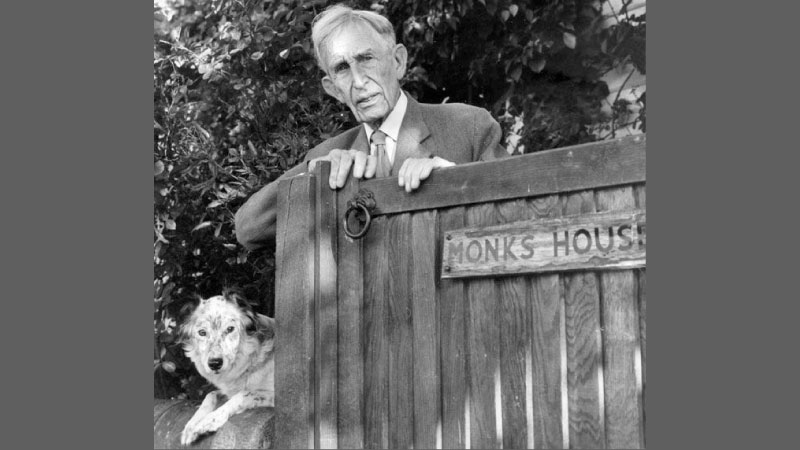

The Sinhala translation of diaries of the well known colonial administrator cum creative writer Leonard Sydney Woolf (1880 – 1969) is significant due to several reasons. The Sinhala translation by the translator Chandrasri Ranasinghe is titled as ‘Leonard Woolfge Dinapothe Nila Satahan’ (Jayakodi 2018) enters the book scene at a time when the Sinhala translation of his well known novel ‘A Village in the Jungle’ known to the Sinhala reader as Baddegama is prescribed as a text for several local examinations.

The translation of Woolf’s novel as well as the original work paved the way for several discussions on the role of the colonial rule as well as its outcome into the postcolonial literary activities on the part of several scholarly administrators such as Henry Parker, Hugh Neville, Emerson Tenant, Codrington and several others. Their profiles, as well as the works, became known not only to the local readers but also to the general English reading world. This resulted in the knowledge of the local culture inclusive of religious susceptibilities and cultural affiliations.

Nuances and patterns

The colonial rulers had much to gain as they gradually embraced the sensitive socio-religious nuances of the patterns of living and attitudes of the local masses. The translator’s preface to the selected diary entries that cover the period 1908 – 1911 is resourceful as it underlines various reasons for the genesis of the works.

The preface attempts to overview the arrival of the writer cum administrator Woolf to Ceylon in 1904, commencing his work in Jaffna Katcheriya. This account is followed by a short biography of Woolf presenting his background biographical details pertaining to parentage and academic career. The reader is made to know his intimate links with his wife the well known creative writer Virginia Woolf (1882 – 1941) and the struggles they encountered as a result of the various social upheavals.

This is followed by Woolf’s journey to Hambantota down south assuming more and more day to day work meeting various types of people. This is the starting point of his diary writing that he kept in keeping with fivefold vision.

1. Gauge the exact type of work he was engaged in the daily routine.

2. Keep a record of some of the day to day experiences faced during a day.

3. Third, he was interested in keeping a record of some of the strange experiences of other people whom he encountered. They covered not only the known officials connected to his colonial duties but also others as well.

4. The types of regulations that he had to undergo during the performance of his duties as a chief colonial administrator. This segment includes the types of agreement as well as disagreement that he had to face with his own people as well as the minor officials.

5. He makes notes of his various punishments imposed on his subordinates as well as those who were branded as lawbreakers and tax dodgers.

Self-disciplined visionary

This plays a vital role as a sense of inspiration to write his narrative ‘A Village in the Jungle’. By way of a self-disciplined visionary, he held the colonial administrator’s way of spending the time in the following way:

“To be born again in this way at the age of 24 is a strange experience which imprints a permanent mark upon one’s character and one’s attitude to life. I was learning in England, everyone and everything I know I was going to a place and life in which I really had not the faintest idea of how I should live and what I should be doing.” (Growing)

Perhaps out of sheer interest in self-introspection, Woolf detoured from mere conventional diary entries of an administrator and left a brand for himself as a creative writer. This is visualised in some of the personal attitudes as entered in the form of diary notes. As such the result was not a mere official document but a creative process that transcended the seal of an administrator.

Imperialism and colonialism

It looks as if Woolf had a deep sense of perceiving various political concepts as they changed over the years. In his monograph titled as ‘The Journey not that arrival matters’, he stated that “Imperialism and colonialism are today very dirty words, particularly East of Suez. I hoped if I revisited Ceylon, to be able to go to the places where I had worked as a government servant and see something of how now that Ceylon was a sovereign independent state their administration compared with ours. But to do this, I would need to have some help from the Sinhalese and Tamil administrators of today, and I feared that I might find them not unnaturally, contemptuous if not hostile. Would they not say, or at any rate think: “Fifty years ago, you were ruling us here, an insolent, bloody-minded racialist and imperialist. Thank God, we have now got rid of you and really we don’t want to be reminded of how you lorded it over us and exploited us.”

With the exception of a few, all diary entries of Woolf are paved down to the minimum brevity. This enhances in the quality of readability. A discerning scholarly researcher may find a fund of invaluable resource material to pay heed to such aspects as intercultural and interracial issues. Further, the diary entries include sensitive areas such as poverty, hunting, agrarian factors, love, marriage, sicknesses, punishments, repentances, addictions to drugs and liquor, murder, hatred and ill will and legal disagreements. The clarity of thinking and the equivalent clarity in expression are seemingly the hallmark emblem that captures a certain degree of depth in these diary entries.

Add new comment