If I ever meet Haruki Murakami I would get on well with him. He loves cats. When a reader once asked him, “Do you think cats can understand how humans feel? My cat Bobo ran away when she saw me crying.” The novelist told her: “I suspect that either you or your cat is extremely sensitive. I have had many cats, but no cat has ever been so sympathetic. They were just as egoistic as they could be.”

He also thinks coincidence in a novel is not a bad thing. When asked why he was so keen on using coincidence in his novels, when so many writers tried to avoid them because they often seemed unlikely to readers, he said, “Dickens’s books are full of coincidences; so are Raymond Chandler’s: Philip Marlowe encounters numerous dead bodies in the City of Angels. It’s unrealistic – even in LA! But nobody complains about it, as without it, how could the story happen? That’s my point. And so many coincidences happen in my real life. Many strange coincidences have happened in many junctures in my life.”

Yet, he has other obsessions that I honestly can’t share with him. He is obsessed with the elephant. The refrigerator. The cat. And the ironing! (He loves ironing anything and everything). The other is his strange dream. “It’s my lifetime dream to be sitting at the bottom of a well”, he said to John Mullan once in an interview. The reason, in his eyes is quite logical, “I thought: I can sit at the bottom of a well, isolated … Wonderful!”

Yet, he has other obsessions that I honestly can’t share with him. He is obsessed with the elephant. The refrigerator. The cat. And the ironing! (He loves ironing anything and everything). The other is his strange dream. “It’s my lifetime dream to be sitting at the bottom of a well”, he said to John Mullan once in an interview. The reason, in his eyes is quite logical, “I thought: I can sit at the bottom of a well, isolated … Wonderful!”

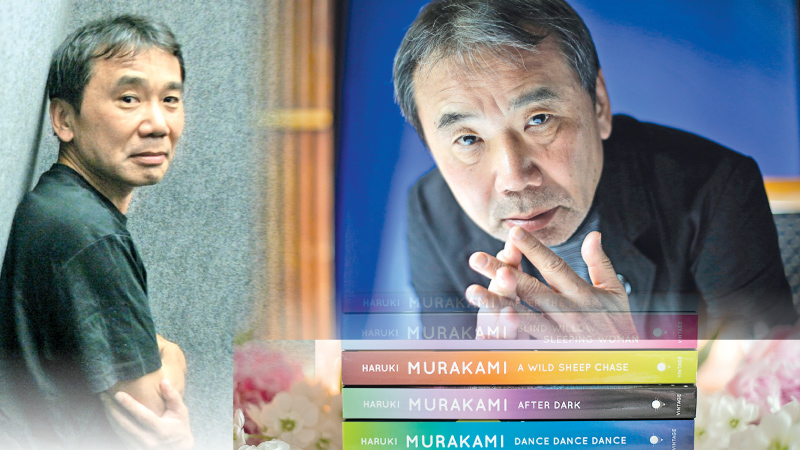

Yet, in spite of these eccentric ways, Haruki Murakami is not only arguably the most experimental Japanese novelist to have been translated into English, he is also the most popular, with sales in the millions worldwide. His greatest novels inhabit the subliminal zone between realism and fable, whodunit and science fiction: he has won virtually every prize Japan has to offer, including its greatest, the Yomiuri Literary Prize. He has also been named the frontrunner for the Nobel prize in literature, which he feels, is a real nuisance. “It’s not like I’ve been officially nominated or anything, it’s just unaffiliated bookmakers who are putting odds on me. It’s not a horse race!”

Born in 1949 in Kyoto, Japan’s ancient capital, to a middle-class family: his father was a teacher of Japanese literature, his grandfather a Buddhist monk, Murakami and his family moved to Kobe when he was two, and it was this bustling port city, with its steady stream of foreigners (especially American sailors), to quote the New York Times, ‘that most clearly shaped his sensibility.’ Rejecting Japanese literature, art, and music at an early age, Murakami came to identify more and more closely with the world outside Japan, a world he knew only through jazz records, Hollywood movies, and dime-store paperbacks. As a student in Tokyo in the late sixties, he developed a taste for postmodern fiction. He married at twenty-three and spent the next several years of his life running a jazz club in Tokyo, before the publication of his first novel made it possible for him to pay his way by writing.

Those who have met him say its hard to come to terms with his megastar reputation and the modest and unassuming writer they meet sometimes in his office in Tokyo, sometimes in a publisher’s boardroom in Loss Angeles. “In person, Murakami looks about a decade younger than he is, the result of a rigorous daily regime of running and swimming that he’s kept up, he says, “for more than 30 years. I’m running almost the same distances as when I was younger, but the times are getting worse.” Affable and polite, he is also given to long silences and the kind of sidelong, suggestive pronouncements that characterise his novels. “Everything is biography,” he says, “but at the same time I have changed everything into fiction.” Most disconcertingly, perhaps, he gives the impression of being just as baffled by his own wayward, metaphysical fiction as his readers are. “It’s very spontaneous, you know,” he shrugged at one point. “I write what I want to write, and I’ll find what I want to write while I’m writing.”

What’s more, he says, he doesn’t like thinking of himself as creative. “I’ve always admired routine and sticking to it, he explains. “However depressed I am, however lonely or sad, routine work helps me. I love it. Basically I think of myself as an engineer or a gardener or something like that. Not a creator, that’s too heavy for me. I’m not that kind of person. I just stick to the routine work.”

A Murakami novel, he says, will start from a single paragraph, “or a sentence, or a beginning visual scene. Sometimes it’s just like video footage. I see it every day, maybe 100 times, or 1,000, over and over. Then all of a sudden, I say, ‘OK, I can write this one.’

The end product is amazing. They say people have published cookbooks based on the meals described in his novels and assembled endless online playlists of the music his characters listen to. A company in Korea has organized “Kafka on the Shore” tour groups in Western Japan, and a Polish translator is putting together a “1Q84”-themed travel guide to Tokyo.

Once he finishes writing a book, Murakami thinks its best not to try to change it, years later. For instance, he wouldn’t dream of improving his best-known novels, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, if he had the chance to write the 30-year-old work again. “When you think about a girl you dated a long time ago, don’t you find yourself thinking, ‘Ah, if only things had gone better,’” Murakami explains. “I often do. It’s the same thing … if only things had gone better. That said, then was then, and I think I did my best.”

Murakami thinks he is a very normal person - sometimes. “I started to write novels and stories when I was 30 years old. Before that I didn’t write anything. I was just one of those ordinary people. I was running a jazz club, and I didn’t create anything at all. But all of a sudden I started to write my own things and I think that is a kind of magic. I can do anything when I’m creating stories. I can make any miracle. That’s a great thing for me. I can say I deal in magic.”

And yet, he also thinks to write well one has to be born with the talent. Writing is like “chatting up a woman”, says Murakami. “You can get better with practice to a certain degree, but basically, you’re either born with it, or you’re not.”

Add new comment