There were of course many influential and profitable newspapers in Ceylon before Wijewardene started the Daily News. There were also outstanding newspaper men who, in their time, wielded considerable power.

Wijewardene was singular in the skilful way in which he brought about the transition from limited circulations to mass production. When he became a newspaper proprietor, readers were to be found mainly in Colombo and the provincial towns. Planters on estates received their papers a day or two after publication. The average daily sale of a paper did not exceed three or four thousand copies. When he died, newspapers were distributed to every nook and corner of the island, carried to their readers by the most modern means of transportation, including the aeroplane. The remarkable increase in literacy together with new methods of production and distribution sent up the circulations of newspapers by leaps and bounds. The Dinamina prints over 70,000 copies a day and the Daily News over 55,000 copies. Wijewardene was in fact fulfilling in Ceylon the same function which Northcliffe had set before himself in England a dozen years earlier.

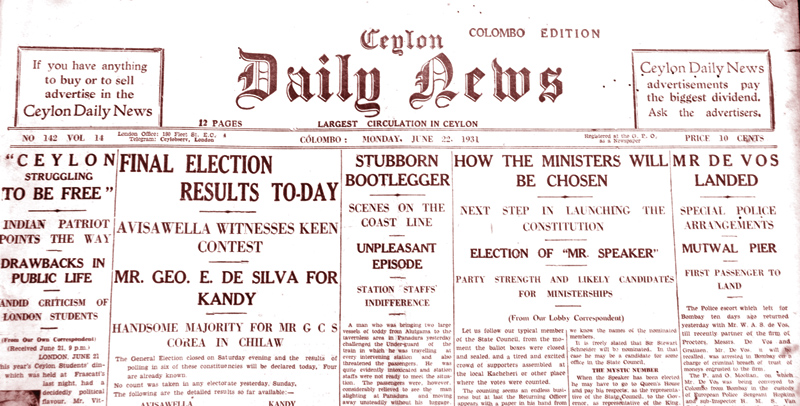

When the Daily News was started there were in existence in Colombo four other daily newspapers published in English, namely, the Times of Ceylon, the Observer, the Ceylon Morning Leader, and the Ceylon Independent. The Ceylon Observer, which Wijewardene acquired in 1923, and the Times of Ceylon, are now both well over a hundred years old. What may be described as the first newspaper in the island was the Government Gazette, still going strong but so different from the Gazette of old whose contents included obituary notices recounting the virtues of departed ones, poetry of varied merit, and interesting and instructive communications on various subjects. Gradually, however, the publication discarded these embellishments and developed into the dull and prosaic weekly of today.

As the subject of this book was probably the most successful newspaper man produced by Ceylon, the inclusion of a brief history of journalism in the island in the present chapter would not be out of place. The era of newspapers independent of Government began with the arrival of Sir Robert Wilmot Horton as Governor of Ceylon in October 1831. Sir Robert was a politician. He had been an Under Secretary of State in England and had married the beautiful cousin of Lord Byron. It was said of him that he was never happy unless he had a newspaper controversy on his hands.

As the subject of this book was probably the most successful newspaper man produced by Ceylon, the inclusion of a brief history of journalism in the island in the present chapter would not be out of place. The era of newspapers independent of Government began with the arrival of Sir Robert Wilmot Horton as Governor of Ceylon in October 1831. Sir Robert was a politician. He had been an Under Secretary of State in England and had married the beautiful cousin of Lord Byron. It was said of him that he was never happy unless he had a newspaper controversy on his hands.

Within three months of Sir Robert's arrival, the Colombo Journal was published under Government auspices and with the encouragement of the Governor himself. It was printed at the Government Press and edited by Mr. George Lee its Superintendent. Mr. Lee denied, however, that the Journal was a Government paper and that the Governor controlled him as Editor. He claimed that its profits covered expenses. Mr. Lee was assisted in the editorship by Mr. Henry Tuffnell, the Governor's Private Secretary and son-in-law. Sir Robert himself was a frequent contributor to the Journal and signed his articles “Timon,” “Pro Bono Publico” and “Liber”. Another contributor was the Treasurer, George Turnour, the gifted translator of the Mahawamsa. The paper was discontinued from the end of 1833, on the orders of the Government in London, after it had run for two years. The reason given was that the field should be left to private enterprise, but it can scarcely be doubted that the Journal's severe criticism of the authorities in London had more to do with the decision.

However, the field of private enterprise was soon occupied, as there was a clear demand for a free newspaper. The merchants of Colombo, Mr. G. Ackland and Mr. E. J. Darley among them, combined to start The Observer and Commercial Advertiser, which made its first appearance on the 4th February 1834. It is the newspaper which Wijewardene bought nearly 90 years later.

Birth of the Colombo Observer

Colonel H. C. Byrde has described the state of expectation at the time: “I can well remember discussions in the Fort, for I had become associated with Messrs. G. Boyd, Ackland and others, and there were speculations as to getting up an exponent of public opinion, and how it was to be done, and who was to pay for it, and who would be Editor, and if it was likely to pay, all of which resulted in the birth of the Colombo Observer under the editorship of the late Dr. Christopher Elliott who was, prior to this, stationed at Badulla as Assistant Colonial Surgeon, which appointed he resigned to come to Colombo”.

The new paper introduced itself to the public thus: “The first number is furnished gratis, inviting those who are inclined to favour a free Press to become subscribers.... at 12 shillings a quarter. We appear before a public, fully aware of the difficulties we have to encounter, and from who we hope for every indulgence, encouragement and support....

“Although we apprehend our type will not be the most pleasing to the sight just now, we trust ere long in that respect at least our paper will vie with any of its contemporaries. For the present we have availed ourselves of such material as could be spared by Government and a Missionary Society, who have kindly afforded what assistance we have required to enable us to commence at so early a period.”

The Observer attacked Sir Robert Wilmot Horton's Government so relentlessly that a defence of the Administration was felt to be necessary. On the 3rd May 1837 appeared the first issue of the Ceylon Chronicle which was privately aided by the Governor and professedly “conducted by a Committee of Gentlemen” - the gentlemen being mainly of the Ceylon Civil Service. It was edited by the Rev. Samuel Owen Glenie, the Colonial Chaplain of St. Paul's and afterwards Archdeacon of Colombo; but the Bishop objected to this partnership and Mr. Glenie retired, to be succeeded by Mr. George Lee who was now Postmaster-General. The Governor, as well as other members of the Service, contributed to the Chronicle. On the other side, in sympathy with the Observer, were Serjeant Rough, Chief Justice, and Mr. H. A. Marshall, Auditor-General. On the 3rd September 1838, the new paper folded up.

Probably the arrival of the new Governor had something to do with the discontinuance. On the 7th November, 1837, the Right Hon. J. A. Stewart Mackenzie became Governor, and with him came, Mr. A. M. Ferguson, who was destined to play so large a part in the history of the Observer. Mr. Ferguson began writing to the Observer at once and the paper became a supporter of the Government. But the disappearance of the Chronicle did not mean that there was an end of opposition to the older papers. The types and printing presses of the Chronicle were sold to Mr. Mackenzie Ross who, on the 7th September, 1838, started the Ceylon Herald (not to be confused with the Kandy Herald of thirty years later). The new paper was a violent opponent of the Governor and the Herald went so far as to impute to him the intention of acquiring large tracts of land at nominal prices. Ross was tried for libel before Sir Anthony Oliphant and a British Jury but was acquitted.

In 1842 the Herald was taken over by Mr. James Laing, Deputy Postmaster at Kandy, who supported the Government. It then passed on to Dr. McKirdy, on whose death it devolved on the Secretary of the District Court. Mr. W. Knighton, who wrote two books on Ceylon, became Editor. In July 1846 it was bought for Sterling Pound 450 by a group of persons who had decided to start a new paper to oppose the Observer. Thus arose the Ceylon Times, now the Times of Ceylon, the first issue of which was published on the 11th of July 1846.

The greatest days of the newspaper were perhaps, those under the Cappers. John Capper had come out to Ceylon to join the firm of Acland and Boyd and became a junior partner in the year 1847 when it had to suspend payments. He left for England in 1851 and joined the London newspaper Globe as sub-editor. He was back in Ceylon in 1858 and acquired the Ceylon Times of which he became editor. In 1874 he sold the property to a limited company, which was not a success, and on its failure, John Capper again became the proprietor on the property reverting to him as mortgagee. Thereafter the paper was a great success. In 1946 it changed hands and was bought by a syndicate for a sum of about Rs. 7 Million.

In 1858, a new Civil Medical Department was formed by the Government with Dr. Christopher Elliott as the first Principal Civil Medical Officer. This involved his severing his connection with the Observer, A. M. Ferguson, who as mentioned already, had arrived in Ceylon as Private Secretary to the Governor, Mr. Stewart Mackenzie, had joined the paper as sub-editor in 1946 and assumed a major share of responsibility in its production. When Dr. Elliott gave up the editorship, Ferguson bought the newspaper. He was joined in 1861 by his nephew John as Assistant Editor and reporter.

For nearly fifty years A. M. Ferguson dominated public opinion in the island. He won the admiration even of his opponents by the fearlessness and vigour with which he conducted the policy of his paper. Among his pet aversions was a fellow Scotsman, Judge Berwick. Berwick was promoted to the Supreme Court and in his new capacity he presided at a session at Kurunegala. There, in trying a man for bigamy, he held that there was no marriage contract as the formula had run: “Will you have this man for your lawful husband?”, when it should have been: “Do you have this man as your lawful husband?” There was no doubt that Berwick was wrong. Ferguson got hold of this and wrote that they could not have such a man as a Judge of the Supreme Court and that he should be removed immediately.

The Governor asked the Attorney-General to state a case against the Editor and send it to the Judges of the Supreme Court for their opinion where Berwick was right in his view that there was no marriage. The Judges held against their colleague. The Observer was jubilant and demanded that Berwick should revert to the lower court to dispense justice there. Berwick once attended a Fancy Dress Ball in the attire of “a Gentleman of the Nineteenth Century”. The Observer commented that “the disguise was perfect”.

Scholar and fine writer

Mr. A. M. Ferguson's younger son, Donald William, was for some years on the staff of the Observer. He was a scholar and fine writer on historical topics. His contributions were of such importance that a weekly supplement was issued gratis from August 1886 in which were published “papers bearing on the past history or development of Ceylon, or concise essays on topics bearing on modern local progress.” No student of Ceylon history can afford to do without the volumes of the Literary Register which Donald Ferguson edited. He returned to Scotland in 1983 and died there in 1910.

John Ferguson's connection with the Observer lasted for fifty-five years. He was a prolific writer on a variety of subjects and was for a time a member of the Ceylon Legislative Council. His son, R. H. Ferguson, was not a chip of the old block and did not make a success of his editorship. He sold the paper to a syndicate of members of the European Association who in turn sold it to D. R. Wijewardene in 1923.

The Examiner was first published on the 7th September 1846 with Mr. Bessell as Editor and Mr. John Capper as chief contributor. It was started by a few British merchants as a mercantile organ and was sold a few years later to Mr. R. E. Lewis of the firm of Parlett, O’ Halloran and Co. Then it passed into the hands of a group of lawyers with C. A. Lorenz at their head. They included Mr. (later Sir Harry) Dias, Jaems D’ Alwis, C. L. Ferdinands and J. R. Dunuwille. In a letter to his friend and colleague at the Bar, Richard Lorgan, Lorenz wrote: “I have purchased the Examiner from John Selby and placed it in the hands of Louis Nell. If, as I hope, we succeed in keeping up the thing, Fred, Louis and myself being a sufficiently strong staff for the purpose, we shall prove after all that Ceylon has arrived at a position when her children can speak out for themselves, and that in doing so they can exercise the moderation which even English journalists have failed to observe”. The paper was powerful and was influential so long as Lorenz was Editor. In 1870 ill-health compelled him to withdraw his active supervision of it and Leopold Ludovici took over the editorship. He was followed by Francis Beven. The paper ceased publication in 1900. Sir Thomas de Sampayo presented a full set of the files of the Examiner to D. R. Wijewardene.

In 1868, a bi-weekly newspaper, the Kandy Herald, was started by some planters. It was printed in Colombo in the offices of the Times of Ceylon, and Richard Morgan used frequently with heavy step to mount the staircase in the Colombo office to dictate an article in defence of Government policy. An early number contained the confidential despatch sent to the Secretary of State by Governor Sir Hercules Robinson on the petition sent to Her Majesty's Government by George Wall and other members of the famous Ceylon League. It was a bitter attack on the planters who were depicted as selfishly bent on securing for themselves the control of the finances of the Colony. The “unauthorised publication” caused a stir in England. Questions were asked in the House of Commons and the Colonial Office was said to have been worried about it. But the Secretary of State, the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, whose attention was drawn to it, laughed away the episode by saying that such indiscretions were not unknown in England.

Sir Richard Morgan, Queen's Advocate, was a member of both the Executive and Legislative Councils and the most powerful person in Ceylon next to the Governor himself. There is an entry in his diary which reads: “I mean to write a series of articles for the Lakrivikirana (a native newspaper with a large circulation) likely to prove essential to the natives: Vaccination, cattle disease, labour on coffee estates, irrigation, etc.”

Sir Richard was also interested, towards the end of his life, in a journalistic project for the benefit of his younger son. He intended calling the paper, the Weekly Serendib. The prospectus, found among his papers, stated that:

“The Weekly Serendib desires in no way to interfere with the other papers. Its aims are different; its efforts will take another direction. The advancement of the natives is its great object.

“It were vain to try to emulate the Observer, with its long and varied experience, its inexhaustible resources, stern firmness and unbending consistency. It has been charged with disregard to the feelings of others, but all this proceeds from earnest convictions………

“The Ceylon Times is, and will long remain, the great commercial organ, a work to which it devotes itself with singular ability, and for which its Editor’s extensive experience and its close and careful study of local subjects eminently befits it…

“The Examiner has our best sympathy. None can withhold sympathy from anything with which Charles Lorenz is connected………”

The Weekly Serendib never saw the light, although arrangements were well advanced for its publication.

The Ceylon Independent had as its first editor George Wall. He had founded a Planters’ Association of Ceylon and played a leading part in the agitation for a more representative form of government. He suffered serious losses during the coffee crash and turned to journalism until he was able to put his affairs in some order. The paper eventually passed into the hands of Sir Hector Van Cuylenburg, Burgher member of the Legislative Council. For some years the Rev. (late Canon) G. B. Ekanayake wrote the important leading articles of the paper. At a still later period it was edited by the distinguished schoolmaster and historian, L. E. Blaze.

The Ceylon Standard was started in 1980 by a group of wealthy Sinhalese. A large amount of money was sunk in the project and an editor and sub-editor recruited from England. Mr. Windus, the editor, died shortly after his arrival and Mr. Wayman, the sub-editor left for Australia. The company went into liquidation and the Morning Leader, owned by members of the de Soysa family, rose on its ashes. The ownership of the Morning Leader later passed to a syndicate consisting of Mr. Charles Peiris, brother of Sir James Peiris, Mr. C. E. A. Dias and Mr. W. A. de Silva. In its last phase it was under the sole ownership of Mr. De Silva.

Academic career

The Morning Leader was a power in the land so long as it was edited by Armand de Souza, father of Tori de Souza, editor-in-chief of the Times of Ceylon, and of Senator Doric de Souza of the Ceylon University. De Souza had an unfailing source of reliable information in Sir Marcus Fernando, for long the eminencegirse of the Governor's Executive Council. So long as his brothers-in-law, the de Soysas, owned the paper, Sir Marcus was able to influence it policy but when it went under new ownership he lost interest in it. After de Souza’s death, at the early age of 47, the paper was edited for a short time by D.L.C. Rodrigo, fresh from Oxford and the London School of Journalism. Wijewardene had intentions of taking him on to his staff but when the editorial chair of the Morning Leader became vacant Rodrigo accepted an offer to occupy it. Not long after he decided that teaching classics was a more congenial calling than churning out editorials and started an academic career which culminated in the Professorship at the University which he held for many years with great distinction. Wijewardene in due course bought the Independent and put the Morning Leader out of business.

The Sinhalese Press had a creditable record. Mention has already been made of the Lakrivikirana, to which Sir Richard Morgan proposed to contribute a series of articles. One of the earliest Sinhalese papers was the Lakminipahana, first public in 1865. The Sarasavisandarasa, which was started by the Buddhist Theosophical Society, had, as its Editor, Pandit Weeragama Bandara who, in the words of Mr. W.A. de Silva, “brought a new spirit into Sinhalese writing. He introduced a fine style, elegant and popular, which created a new era in Sinhalese prose composition.”

Two other Sinhalese newspapers which were popular at this time were the Sinhala Baudhaya and the Sinhala Jatiya. The latter was edited by Mr. Piyadasa Sirisena, a well-known publicist of his day.

H.S. Perera, a resourceful member of the staff of the Sarasavisandarasa, founded the Dinamina towards the end of his life. It was bought by D.R. Wijewardene and his brother “D.C.” – their first newspaper venture jointly or separately. They did so on the advice of D.B. Jayatilaka who by his well-informed articles and personal prestige helped to make it the most influential Sinhalese daily newspaper. Since then there have been several other Sinhalese newspapers, notably the Silumina and Janata, both published by Lake House, the Lankadipa published by the Times group, the Lakmina and the Swadesha Mitraya. The last-named was founded and edited by D.W. Wickremaratchi, who rendered yeoman service to Wijewardene’s Dinamina as Editor and Manager for some years.

The most widely read Tamil newspapers in Ceylon today are the Virakesari and the Thinakaran. Many Tamil newspapers with a more limited circulation have been published in Jaffna, but none f them has been great commercial success although they have played an important part in the social and political life of the Tamils.

The first attempt at journalism in Jaffna was made in 1841, five years before the Examiner and Ceylon Times appeared, when the Morning Star, a bi-monthly Tamil journal, was launched under the editorship of Henry Martyn. The Catholic Guardian was started in 1876. Other newspapers published in Jaffna from time to time included the Ceylon Patriot, the Jaffna Freeman and the Hindu Organ. Batticaloa published a paper called The Lamp.

The Catholic Messenger, published in Colombo, has had a distinguished career and has never been more vigorous than it is today.

Add new comment