In Sri Lankan popular culture, the history of Buddhism on the island is basically unassailable.

Many monks, scholars, and Buddhist lay people believe that Sri Lanka is the world’s cradle of Theravada Buddhism, as shown by the Mahavamsa, the text written by Buddhist monks that stretches back two millennia.

But Professor Osmund Bopearachchi, a University of Kelaniya graduate who is now a professor of Central and South Asian Art and Archeology at the University of California Berkeley, argues that the story is actually much more complex.

Sri Lanka Ports Authority Logistics Director Upali de Zoysa. |

At a recent lecture at the University of Colombo, Professor Bopearachchi said the history of Buddhism in Sri Lanka is more influenced by Mahayana forms and ideas, particularly from South India, than people think.

“The time has come for Buddhist scholars, archeologists, and art historians to examine closely the diffusion of (Mahayana) Buddhism from India to Sri Lanka and then to Southeast Asia and China,” he said.

This cross-fertilization of Buddhist practice was facilitated by ancient maritime trade routes that existed long before the Romans famously began to write of Sri Lanka’s riches, he argued.

“The island of Lanka played a vital role in transmitting merchandise between East and West, and North and South. Because of this, the political, religious and cultural history of Sri Lanka reflect the fluctuations of the markets, changing patterns of trading destinations, and the evolution of Buddhist philosophies,” he said.

Put simply, trade in commodities accompanied a trade in culture, ideas, and beliefs.

This recognition has implications that reverberate even today.

Pre-Roman trade routes

Mainstream histories of Sri Lanka’s importance to maritime trade routes often begin with early Roman descriptions of the island.

The Greco-Roman geographer Ptolemy, for example, drew a map of Sri Lanka in the 2nd century CE. In it, the island appears about ten times its current size, possibly reflecting its geographical importance to ancient traders.

But in fact, long before the Roman Empire took control of Egypt and its valuable Red Sea trade route in 30 BC, India and Sri Lanka were engaged in “a dynamic regional maritime network based on coastal navigation,” Bopearachchi said.

The recent discovery of an ancient shipwreck near the village of Godavaya off the island’s Southern coast is proof of this fact.

“The (wreck), dating from the 2nd or 1st century BC, belongs to a period when Romans were still not engaged with Indian Ocean trade,” Bopearachchi said. This find “has revolutionized our knowledge of the history of maritime trade in South Asia,” he added.

In ancient times, Sri Lanka was trading in precious goods like ivory, tortoise shells, and gems, he said. So when the Romans did begin to navigate the Indian Ocean, they were entering a previously established market.

The Romans took Sri Lanka’s goods all over the ancient world. A blue sapphire discovered on the site of Alexandria on the Caucasus, in modern-day Afghanistan, dating back to the 1st or 2nd century CE, is just one example of this North-South trade, Bopearachchi said.

The influence of Mahayana

But ivory and gems were not the only things flowing along these ancient trade routes. Traders also passed along their religious practices and beliefs.

“During the first three centuries of the common era, South Indian traders played an integral role between Alexandrian traders and Sri Lankans,” Bopearachchi said. “As a result, they came from Andhra and Tamil Nadu to Sri Lanka in search of merchandise.”

He said that while visiting religious monuments in Sri Lanka, these traders would have brought plaques as offerings to the island’s Buddhist establishment.

Professor Osmund Bopearachchi. |

This explains why some reliefs in Andhra style, depicting scenes from the life of the Buddha, have been found in religious monuments of Sri Lanka, he said.

“Cultural interactions between Andhra and Sri Lanka made the Buddhist communities closer,” he said. A branch of the Mahavihara in Anuradhapura was established in Andhra Pradesh, he said, and Mahayana Buddhism flourished at the Abhayagiri monastery.

Indeed, in 2010, while undergoing conservation of the Abhayagiri stupa, archeologists discovered a tablet carrying Tantric Mahayana inscriptions dating to the 8th century CE.

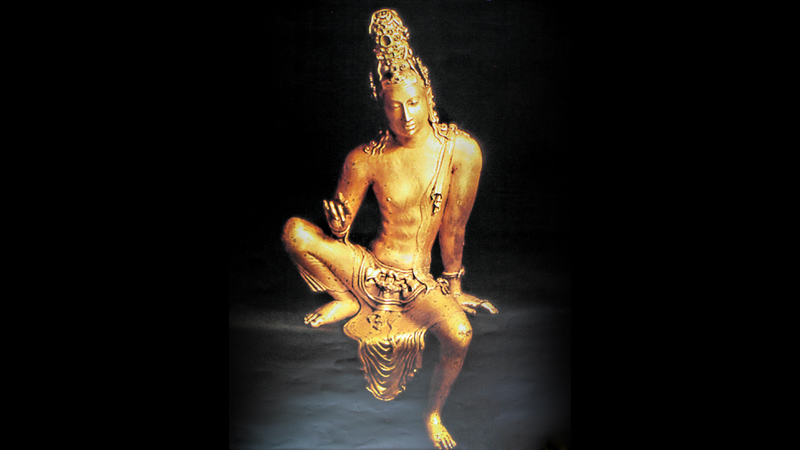

Bopearachchi said that discoveries from around the 7th and 8th centuries show that Mahayana Boddhisattva statues actually outnumbered Buddha images on the island. They are scattered along the island’s ports, rivers, and overland routes.

Because the Boddhisattva Avalokitesvara was believed to be the protector of sailors and travelers, the presence of Boddhisattva statues “shows widespread Mahayana practice” in Sri Lanka, he said.

Professor Justin Henry, an American scholar of religious history, takes a more textual approach to the history of Buddhism in Sri Lanka. But he agrees with many of Bopearachchi’s positions.

He said that medieval kings are sometimes identified as Boddhisattvas in various texts and inscriptions. “The inscriptional, art-historical, and literary record of the 9th and 10th centuries evidences an injection of Mahayana imagery and vocabulary into Sri Lankan Buddhism that would have enduring effects,” he said in an interview.

It is in this context of hybridity, the historians argue, that the famed spread of Buddhism east from Sri Lanka to Southeast Asia must be understood.

Buddhism on the move

In the 7th century, trade between Chinese, Arab, Persian, and South Indian merchants exploded, connecting Sri Lanka to Southeast and East Asia in new and profound ways.

“It was with the sudden burst of trade activities between China and the Middle East in the 7th century that Sri Lanka began to play a decisive role between East and West,” Bopearachchi said.

Sri Lanka’s increased importance in the context of trade also meant a wider spread of its religious beliefs and practices.

An emblematic story is that of Vajrabodhi, a South Indian Vajrayana Buddhist monk. Vajrabodhi eventually went to serve in the Tang Court of 8th century China.

En route to China, Vajrabodhi stopped in Sri Lanka, to pay homage to the tooth relic at Abhayagiri and to climb Sri Pada and worship the Buddha’s footprint, according to a biography written by his disciple.

Leaving Sri Lanka from modern-day Beruwala, he was accompanied by 35 Persian ships trading in precious stones.

This episode is a case study in the “diffusion of Buddhist thought and information on maritime trade in the Indian Ocean,” Bopearachchi said.

Pre-dating Vajrabodhi even, King Mahanama in the 5th century sent Sinhalese Buddhist nuns to preside over an ordination ceremony in China during the Song Dynasty.

Sri Lanka made contact with Thailand in the same century, Bopearachchi said, and “close links between Sri Lanka and Burma certainly paved the way for iconographies based on Pali literature.”

He said Pali may have even served as the lingua franca between the two cultures.

“The spread of Buddhism from South Asia to Southeast Asia is closely connected to the growth of maritime networks based on trade that facilitated the movement of Buddhist merchants, traveling monks, and traders,” he said.

Where is Sri Lanka now?

Other scholars and historians think that the lessons of Bopearachchi’s argument have implications on culture and trade today.

Professor Emeritus Gamini Keerawella, the Executive Director of the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies, said he believed it was important to push back against the “very parochial, very narrow” modern view of history.

That view is often “misused to explain present political developments,” he said. Examining current phenomena, like China’s “One Belt One Road” development initiative, should not be viewed through a simplified lens.

Instead of the popular notion that the belt and road are indicative of a resurgence of Chinese imperial ambition, it should instead be analyzed as complex and rooted in a variety of internal and external political factors, he argued.

Senior Professor Amal Kumarage, of the Department of Civil Engineering at the University of Moratuwa, said he was shocked that there were 35 ships anchored at the ancient harbour near Beruwala. “I’m not sure Hambantota has had that many,” he said.

But Sri Lanka Ports Authority Logistics Director Upali de Zoysa pushed back. “To attract traffic to a new port it takes time,” he said. “Aided by a Chinese plan to develop an industrial zone around the port, it will take 10-15 years to get off the ground,” he said.

Meanwhile, Hambantota is surrounded in myriad of controversies that sometimes sloppily mix arguments of sovereignty, foreign intrusion, domestic political strife, and debt. The situation, which has trade at its root, is inextricably linked with culture and history. It will be the job of future historians to untangle the threads.

Reflecting on ancient trade routes, it’s clear that “Sri Lanka was the centre of the world,” Bopearachchi said at the academic forum.

“Still we have a role to play,” he said. “And it is still central.”

Add new comment