In a study published on June 14, 2017 in Science Advances, Dr. Woo and his team show how they successfully replaced blood with microsocopic cyanobacteria, plant-like organisms that also use photosynthesis. By co-opting the process to help heal damaged heart tissue, the team was able to protect rats from deadly heart failure. Fixing an ailing heart, it seems, may be as simple as shining a light on the situation.

Heart disease is the number one killer worldwide. It happens when something blocks blood flow to the heart, cutting off oxygen from reaching this crucial muscle.

For cardiologists, the challenge for preventing subsequent heart failure is to rapidly supply damaged heart tissues with oxygen and nutrients. If we look at nature, photosynthesis answers that question.

If a damaged heart were photosynthetic, it wouldn't need to rely on blood to resupply oxygen and sugar to its tissues. All it would need was the sun. You would enable light to become your fuel source, instead of blood. Researchers tried the next best thing: injecting it with plant-like bacteria.

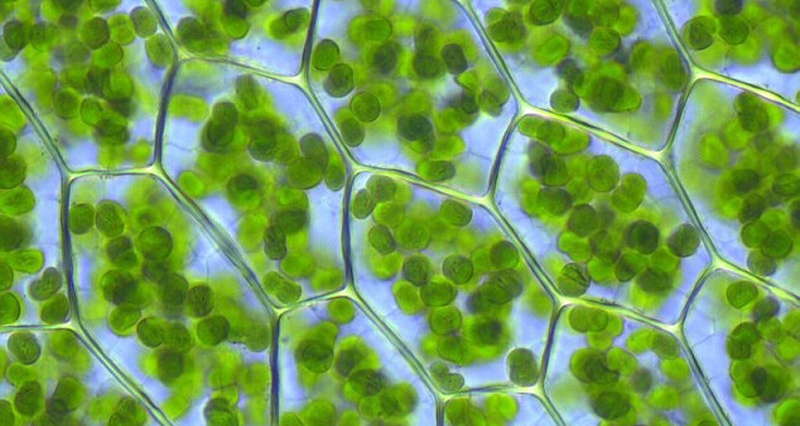

Dr Woo and his team started by grinding up kale and spinach to harvest chloroplasts, the organelles within plant cells that carry out photosynthesis. They were trying to separate out the chloroplasts, the photosynthetic organelles within each plant cell, but found that once isolated, they quickly became inactive. That's when the researchers learned about Synechococcus elongatus, a photosynthetic organism that Golden and other researchers have long used to study circadian rhythms. It has been used recently to produce biofuels, but this may be the first time the cyanobacteria have ever been used in a medical setting. What researchers needed instead were self-contained photosynthetic machines, would could function as miniature greenhouses for the heart.

Cyanobacteria, the tiny organisms, make a living by taking in carbon dioxide and water and spitting out oxygen. In the ocean, they're at the base of the food chain, making the oxygen and sugar that's quickly exploited by other hungry organisms. With help from Stanford microbiologists, Dr. Woo and his team grew a strain of Synechococcus in their lab and injected to the impaired heart tissue of a living rat.

Then, they turned up the lights. After 20 minutes, they saw increased metabolism in damaged areas. Overall cardiac performance improved after about 45 minutes. The evidence suggested that the oxygen and sugar Synechococcus created through photosynthesis was enhancing tissue repair.

After injecting living bacteria into a body organ, you might expect an infection. But interestingly, the researchers didn't find any immune response after a week of monitoring. ‘The bugs are just not there any more; it disappears,” says Dr. Woo. “And maybe that's the best kind of bacteria” - a friendly helper that sticks around to do damage control, then disappears without a trace.

One potential problem with making this procedure a viable treatment is its timing and complexity. Treating heart attacks is a race against the clock, and by the time patients are transferred to a special facility equipped to inject cyanobacteria to the heart, it might be too late. It requires a tremendous amount of investment and technology.

However, the fact that the researchers still saw healthier hearts in rats that underwent treatment after a month could be a promising result. If everything goes the way researchers want it, it would be a huge therapy for people who have had heart attacks.

Dr. Woo and his team reason that Synechococcus balances a chemical equation upended by a heart attack. Using light as fuel for food may be a novel concept for a human heart, but it's old hat for cyanobacteria in their natural habitats.

The recent study is merely proof-of-concept, but scientists are now on the path to trying the technique in human subjects. Next they'll try it in larger animal models that are closer to humans, and they're working on ways to deliver and shine light on cyanobacteria without an open heart surgery. They're even considering genetically editing Synechococcus to make the critters release more sugar.

For many cardiologists, the root of the problem lies not in managing heart attacks after they occur, but in preventing them in the first place.

While these data provide a new and possibly efficacious way to preserve cardiac function after an acute heart attack; the main drawback is, of course, that the SE bacteria must be exposed to light to undergo photosynthesis. While the technique of using some form of SE bacteria is certainly still in the preliminary stages, it is an innovative means of improving heart function and perhaps preventing the damage to the heart muscle consequent on an interruption of blood flow.

Add new comment