They’ve won Oscars, Pulitzers and Nobel peace prizes: eight women at the top of their game tell us how they got there

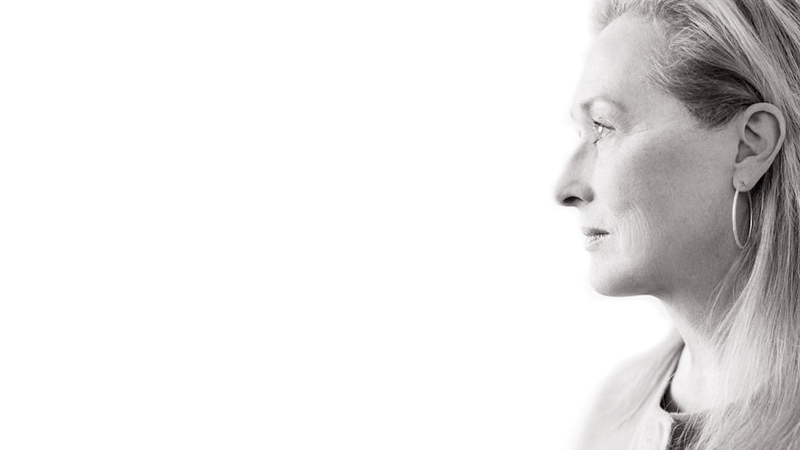

Meryl Streep has been nominated for more Academy Awards than any other actor, and has won for Kramer vs Kramer, Sophie’s Choice and The Iron Lady. In 2015, she sent every member of Congress a letter supporting a proposed amendment to the US constitution to mandate equal rights for women; the amendment was not passed.

“I didn’t always want to be an actor. I thought I wanted to be a translator at the UN and help people understand each other. Some young people come into acting because they see it as glossy and heightened and more sort of divine than their existence; but what interests me is getting deep into someone else’s life, to understand what compelled them to move in one direction or the other. That other stuff, I’ve never liked. My mother used to say, “People would give their right arm to walk down that red carpet. Enjoy it!” You just can’t change who you are.

“I didn’t always want to be an actor. I thought I wanted to be a translator at the UN and help people understand each other. Some young people come into acting because they see it as glossy and heightened and more sort of divine than their existence; but what interests me is getting deep into someone else’s life, to understand what compelled them to move in one direction or the other. That other stuff, I’ve never liked. My mother used to say, “People would give their right arm to walk down that red carpet. Enjoy it!” You just can’t change who you are.

The influencers in our industry are overwhelmingly men: the critics, the directors’ branch of the Academy. If they were overwhelmingly female, there would be a hue and cry about it. Women have 17% of the influence, more or less, in every part of the decision-making process in the industry and, inevitably, that’s going to decide what kind of films are made. But the material that comes to me is still interesting. I’m 67, so mostly I get things for people that age, and there are wonderful projects that would never have existed even 10 years ago. Twenty years ago, I would have been playing witches and crones.

Daughters of Eve, Co-founder, Nimco Ali |

Going from job to job, never knowing where the next one would be, has allowed me to spend time with my four kids – more than if I’d worked at a desk job. That’s a really tough gig, and I don’t know if I could have had four kids and done that. Decisions I made in my career were not always based on aesthetic criteria: was it near, was it going to be shot in the vacation? You make all sorts of compromises in order to have this other thing that you value. My girls and my son and my husband are all way too much in each other’s business, I would say, but we’re close and that’s important. I always tried to stay challenged and work hard, but also keep my hand in and stir the pot at home.

I spent far too much time when I was younger thinking about how much I weighed. If I could go back, I’d say, “Think about the bigger picture.” Of course, it’s a visual medium. We think about our looks. I don’t bring a suitcase with my dossier in it to an audition, I bring my body, so you can’t moan about the fact that you’re judged on your looks: it’s showbusiness. But the other thing is that you’re representing lives, and lives look all different ways and shapes. That’s one thing I do see changing, and it’s really good. It makes the cultural landscape richer.

Nimco Ali was born in Somalia. She is the co-founder, with Leyla Hussein, of Daughters of Eve, a non-profit organisation that supports young women from communities that practise female genital mutilation (FGM).

“”I had FGM as a seven-year-old, and later saw girls going through it, but I didn’t join the conversation. Then I started to see my silence as complicity. Around 2010, I moved to London and came across people working around FGM, but I couldn’t see what they were trying to achieve. I wanted to educate people, yes, but this isn’t a question of ignorance; it’s organised crime. I got together with Leyla, and we started to do more with MPs.

I want to place the responsibility in the hands of the state. I’ve seen community work being done for years, and it doesn’t work. It’s not up to communities to police themselves.

MP, Mhairi Black |

People were saying, “How can mothers allow this?” but I was saying, “How can you, as a citizen of this country, know a five-year-old is about to be cut and stand by because you’re afraid to offend her community? You’re telling that child she doesn’t matter.”

It was early 2011 when I first said, “I’m Nimco and I’m an FGM survivor.” A lot of people were shocked. But I didn’t want to be treated with sympathy: I wanted to talk about survivors, not victims, and I wanted to prevent it.

First came redefining FGM with the Home Office as an act of violence; then defining it as child abuse. It was a way of saying to these girls, “You’re British and we care about you as much as anyone else.” My vagina is British; it doesn’t have a different passport.

The first time my picture appeared in a newspaper, I had death threats. I stayed in bed for two days, wondering, “Is it worth it?” But then I felt guilty. If a girl goes through infibulation and then disappears, we never find out. If something happens to me, at least someone will know.

Having friends I can talk to has been an immense help. A girl came up to me on the tube and said, “Are you Nimco, the girl who talks about FGM?” And I thought, “This is where I get spat on.” But she wanted to thank me. I don’t think of myself as a leader, but as part of a chain. If it wasn’t for all the amazing women who came before me, I wouldn’t be able to do any of it.”

Samantha Power moved to the US from Ireland when she was nine. Her first book,A Problem From Hell: America And The Age Of Genocide, won a Pulitzer prize. In 2013, she was made US ambassador to the United Nations.

I had recently graduated from university in 1992 when I saw images in the New York Times of bone-thin stick figures in camps in the former Yugoslavia – images I didn’t think one could see in the 90s. I wanted to help, but didn’t have any skills. I had been a sports reporter in college, so I decided to try my luck at being a war correspondent. It was a bit of a crazy idea, but a lot of young people were doing the same thing, because they felt horrified and powerless.

I’m not great at languages, but I’m great at talking, and my stubborn desire to communicate with people got me to the point where I could do interviews in the local language. I wrote about my experience, and looked at why the US did what it did when faced with genocide in the 20th century. One key conclusion was how hard it was to effect change. But it still felt as though no other organisation could make an impact like the US government. It seemed to me it would be more efficient to be inside the government than on the outside, throwing darts.

These weren’t steps on a conventional path, and my advice to young people would be not to decide on a job title and script a path toward it, but to develop your interests – go deep instead of wide.

I’ve tried to inject individual stories into everything I do: real faces and real people. Empowering women to get involved in government and diplomacy brings a different set of perspectives, which benefits everyone. This isn’t a theory, it’s a fact: according to the UN, women’s participation increases the probability ofpeace deals lasting 15 years by 35%.

My son was born in 2009 and my daughter in 2012, and I hope, as a result of this job, they’ll be more empathetic, more globally curious. My son is a big baseball fan, as am I, and when I’m finished, we’re going to travel the US and see a game in each of the different ballparks. I hope to make up for some of the lost time.

United Nations, US Ambassador, Samantha Power

|

Mhairi Blackis the SNP MP for Paisley and Renfrewshire South. In 2015, aged 20, she became the youngest British MP since 1667.Her maiden speech in the Commonshad 11m views online.

I was brought up in Paisley: it was Mum, Dad, my older brother and me. We used to go on caravan holidays to the north of Scotland. My mum’s mum had 13 children, so I had lots of cousins to play with.

Our family has always been politically aware: my grandparents were involved in trade unions and Mum and Dad were teachers. When I was eight, my parents, brother, aunties and I marched against the Iraq war in Glasgow. Tony Blair was in town for the Labour party conference, but apparently he got word of the march, so, by the time we were marching past the building he’d disappeared in a helicopter. I remember finding that really unfair, even at eight.

Inequality of any kind is the thing that drives me. I always look at who is losing out, and why. Everything I am interested in boils down to the fact that there’s an injustice happening somewhere.

When the independence referendum was announced, I was a “yes” voter, and I thought, if there was ever a time to join a political party, it’s now. After we lost the referendum, a couple of folk in the local SNP party were saying I should put my name forward to be a candidate, and I said, “Don’t be daft. I’m 20. What do I know about life?” I was giving myself the sort of criticism that other people give me now. People in the constituency started challenging me, saying, “Why is that a bad thing? Surely parliament should represent everybody.” And I thought, “That’s a good point. OK, I’ll go through the vetting process and see if I pass.”

I had no idea what to do after university, but I think it’s good to try things and, if you’re good at them, keep going and see how far you get. Mum and Dad taught my brother and me to have confidence in ourselves, but never arrogance – there’s a fine line. Confidence comes from giving yourself credit when it’s due. My parents always said that as long as you know your stuff and you know what it is you’re going for and why, and if you’ve practised hard and think you’re good enough, then, by all means, stand up and make sure you’re counted.

I’ll be happy if, in five years’ time, I can say, “The place I am representing has been better represented than it ever was before.”

I think part of the problem with politics has been people viewing it as a career. You shouldn’t be in it in order to become first minister. It has to be for a purpose, and it has to be in the present.

Leymah Gboweeis a Liberian peace activist. In 2002, angered by the civil war, the then 30-year-old social worker and mother of four (she now has seven children) organised a march on the capital, with a sit-in that lasted months, leading President Charles Taylor to agree to peace talks. The women’s actions led to the removal of Taylor and the inauguration of Africa’s first female president,Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, with whom Gbowee shared the Nobel peace prize in 2011.

“I was 17 when the civil war started. I had just finished high school and was planning to be a doctor, but the war upended everything. I did a three-month social work course, because that seemed the most immediate way to help. In time, I worked with former child soldiers. I was in one village when the government sent in a truck to abduct children and teach them how to use AK47s. I was with the mothers, watching their children being taken.

By 1998 I had met activists from Sierra Leone who claimed that women could change things, but it was only when I began to work with the wives of ex-combatants that I saw what they meant. The ex-soldiers were often very violent and angry, but their wives stood up to them.

There was a lot of work to do to create a movement that would have some impact: it took us two and a half years. The important thing was that we had no political agenda: we had a shared vision for peace. We were there because we cared about our families.

In 2002 we marched on the capital, Monrovia. There were thousands of us. When we started a sex strike, it became a huge story, and an opportunity for us to talk about peace.

Then, when it was clear that nothing was coming of the peace talks in Ghana, we went to the hotel where they were being held and said we would disrobe. This horrified people: to see a married or elderly woman deliberately bare herself is thought to bring down a terrible curse.

We were able to use things that were ours – our empathy, the ways we are perceived – to make the men listen. It is important we understand our strengths, because in war, the rape and abuse of women and children are seen as ways to demoralise the enemy, to show them they are unable to take care of their families.

It is no longer an option for women to say, “I’m not a politician.” We need to up our game. The age-old excuse has been that we can’t find the good women. It is time for the good women to step up.

-theguardian.com

Add new comment