Constitutional bias – a hindrance to reconciliation

Contradicting the higher values of good government was the 1972 constitution that dislodged the effective functioning of the governing tripod -the legislative, executive and judiciary, bringing this country to a point of no return,though now a somewhat snail’s pace attempt is being made to circumvent past misgivings. For instance the setting up of the Independent Police Commission, very much a cause espoused by Speaker Karu Jayasuriya is a giant leap in the move towards moral government. It certainly is not a factual misnomer to call the 1972 constitution an emotional one that fell short of rational thinking, though it is widely acclaimed that the one who crafted it, Dr. Colvin R de Silva was a man of ‘sound judgement’ noted for his very meticulous reasoning power and legal brilliance. Unfortunately though, she did perform well in certain areas of state enterprises, Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike’s sense of perception is highly questionable because it was her licensing that enabled this constitution to become legally operational. Viewed as a ‘ demi god,’ the mere mention of Colvin (as he was popularly known) invites raised eyebrows and dropped jaws in social circles even today that view him as a legal giant. This is true only as far as his legal gymnastics would stretch where successive ‘victory of the brief’ never mind the moral bearing,was to his credit. After all, a legal victory may not always be a moral one. Against this backdrop, his ability as a legal luminary even his enemy must ungrudgingly accept for that was his forte however, despite the fact that legal brilliance and moral eminence are two distinct elements that do not always synchronize.

|

| Dr Colvin R De Silva |

It was most unbecoming of his astute legal mind to have thrown over board the moral element by politicizing the three arms of government namely the independence of the judiciary, executive and legislative in the infamous constitution he crafted. Political appointments became widespread. The independence of the public and judicial services commissions became a thing of the past. Public servants that were one time men of moral honor ceased to be while corrupt elements replaced them that went down on their knees to politicians. A breed that stood up to the might of politicians in the star studded gentry comprising the Ceylon Civil Service was made defunct only to be replaced by a spineless Sri Lanka Administrative Service membership that crawled before the politicians to fulfill personal aspirations.

In his polluted political venture of a corrupt ’72 constitution that fell short of elegant governance, a certain social class rooted in the southern geographical region became conspicuous, that later comprised the country’s socio/economic/political and religious elite-the ‘nobodies’ that became ‘somebodies.’ It is grossly unfair to state that it was the minorities only that faced discrimination in all fields of activity. Those outside this socio/geographical arena among the Sinhalese also faced discrimination who could not give vent to such, whereas the Tamils and Muslims unreservedly could. Differences of caste came into play and to this day remains a discreetly operative yet very strong factor in the Sri Lankan social whole, impeding progress.

The good news is that the Colebrooke/Cameron reforms facilitated the rise of the Karawe caste and their equivalent but the ’72 constitution helped through politicization an increase in their numbers in all spheres of activity that sidelined the upper caste Govigama Sinhalese. The ‘ape man’ or ‘our man’ culture is amply portrayed in the ‘The rise of the Karawe caste’ - a book that vividly portrays Karawe consolidation as the island’s socio / political/economic landscape transformed into what it was not. Though not openly discussed, the tussle continues even to this day and behind political scenes are caste disputes that weigh down this country’s development agenda. If one thinks ethnicity alone to impede national progress, it is a misconception for caste differences far outweigh what ethnicity has to offer in retarding national growth.

As intellectual celebrities such as Thomas Aquinas, Locke, Hobbs and Montesquieu insist, equity, fairness and reason comprise natural law which law many do not abide by when discriminating people. Natural law it is said is governed by cosmic force on which human conduct ought to be based. The ‘72 constitution, studied in-depth, violates the elegance of what natural law has to offer. It would augur well if future constitutionalists revolve their thinking in terms of reason based natural law instead of emotion based laws for political mileage that carry the potential of creating mayhem by dislodging from egalitarianism, so vital for national development. Natural law calls for a moral sense of doing the right thing. The ’72 constitution which moves away from the independence of the judiciary, executive and legislative into a high speed on the road to politicization does not conform to doing the right thing – a star studded element in natural law that saw this country in shambles in the years that followed by way of rule of law.

| For instance the setting up of the Independent Police Commission, very much a cause espoused by Speaker Karu Jayasuriya is a giant leap in the move towards moral government. It certainly is not a factual misnomer to call the 1972 constitution an emotional one that fell short of rational thinking, though it is widely acclaimed that the one who crafted it, Dr. Colvin R de Silva was a man of ‘sound judgement’ noted for his very meticulous reasoning power and legal brilliance. |

To further wound the existing injury is the prohibition ofdiscriminatory legislation in article 29 making the 72 constitution’s moral element questionable. It even calls for a re-thinking of Dr. Colvin R .de Silva’s moral bearing as a man of stature. Politicization itself is an open invitation to discrimination and a constitutional insistence prohibiting discriminatory legislation overlooks justice and fair play.

The removal of the second chamber known as the Senate where diversity was held sacred is also noteworthy. Unrepresented forces such as ethno / religious minorities, intellectuals that could be expressive in national development ceased to be as they were viewed as trouble makers and a hindrance to progress. While they were seen as a ‘headache’, politicization of government was viewed as ‘sacrosanct.’

The convergence of political authority and the resultant distancing of the electorate contradicted the very vitals of a liberal democracy though the island itself ironically later came to be known as the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. Freedom to express views-an essential of a functioning democracy was ’laid to rest’. This second chamber was a watchdog to unfair legislation whereby what was not in national interest was put on hold, debated and decisions taken after reaching consensus - a reflection of the democratic spirit. An agency of the people’s voice itself was axed which ran contrary to the people’s sovereignty.

The judicial review of legislation was also culled in this constitution where the Power of the courts to challenge any decision taken by the executive and administrative arms of government made non-existent. Though the constitutional architect speaks so vociferously of people’s democratic rights, this concept only skidded and in no way enhanced that ideal. Yet ironically, the judicial review in the intended constitution will not be by the supreme court of this land but by a constitutional court outside the courts system supposedly where lawyers will find no place. This exercise would certainly guarantee the ‘being on par status’ of the total withdrawal of such review in the ’72 constitution. Such manipulative tendencies when crafting constitutions are sure to accompany a ‘bounce back‘ effect for the loss of morality, for a moral conscience needs to be the guiding light in constitutional crafting.

The minority rights safeguards introduced in the Soulbury constitution was withdrawn and legislation against discrimination adopted akin to from the frying pan into the fire as it were. As a result, we see the steady rise and consolidation of the state’s involvement in majoritarianism. On the one hand we see authoritarian rule seeping in and that rule being cushioned by majority rule.

Ironically, this ’72 constitution referred to as autochthonous or home grown was far removed from being home friendly, for it carried with it the potential of destroying both ‘home and family’ which even the given constitution of Lord Soulbury did not offer. The country went down the precipice of misrule and ethnic ties further distanced. We as a people suffer from an irreversible mental condition fascinated by terms and status consciousness. Were we to become a better country under the new term republic simply by untying a political knot linked to Britain over the years? The present quagmire in which we are, will speak unreservedly, whether home grown was far better than the foreign imposition?

Interestingly, the now belligerent Chandrika Kumaratunga’s stony silence at that time is an acid test of her political integrity. Like the proverbial ‘as quiet as a church mouse’, she did not even murmur when before her very eyes the disaster filled ’72 constitution received legal sanctioning. She who is overwhelmingly concerned today on moral politics had nothing to offer then.

No doubt Colvin’s constitutional rag whipped up already existing communal tendencies. Instead of all inclusiveness, a high degree exclusiveness and exclusion arising thereof was evident, moving away from the lofty egalitarian concept where ’majority rules‘ took center-stage. Not surprising then that this was an open invitation to Tamil minority resentment. This is not to condone Prabhakaran’s atrocities against innocent Sinhalese for they, not even in the least are be blamed for the unjust and evil legislative enactments that came off Sinhala politicians to consolidate power. Vehement agitation for constitutional reforms may have been a favourable alternative to win international support. Reconciliation is not to be as long as heavily biased, one sided constitutions are operative. The Tamil ethnic minority must also realize however discriminatory that may be, the international community will only recognize the existence of the state – Palestine a good example and the recent Catalonia upsurge. For instance France categorically refuses support for Catalonia’s break-away from Spanish rule.

Probably against this backdrop, reason has dawned on Tamil politicians even though late that building up a moral force from within is needed instead of resorting to what is physical. Retrospective thinking reveals the futility of the latter. This, combined with constitutional innovation on the part of the government hopefully will see a lasting peace, provided such creativity is not tainted by the schemy agendas of ruling politicians as we see in the intended judicial review.

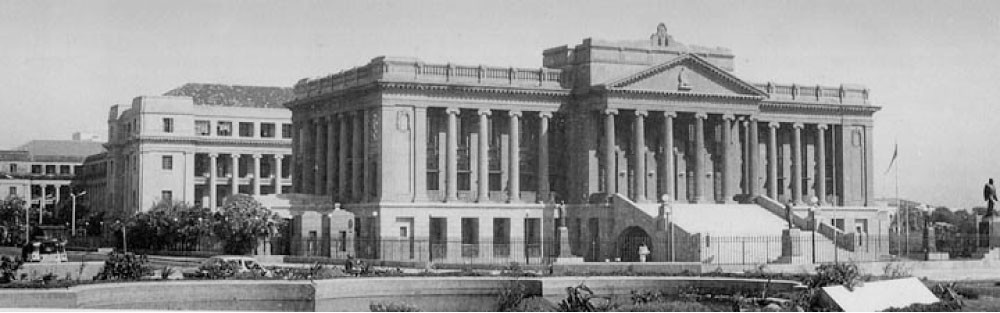

|

| The making of the 1972 Constitution |

Wigneswaran’s novel move in seeing the Buddhist prelates is a positive sign which Prabhakaran’s wouldn’t even dream of in building up that moral force. Wigneswaran was up the right street. It certainly is a moral challenge now to Sinhala extremists to display an attitudinal change in their hardliner approach. It was the first time ever; a Tamil politician visited the citadel or Bastille of Sinhala Buddhist thinking to explain all about devolution-not necessarily as he said federalism. It was a warm welcome that he got from the upper caste Malwatte priest but unfortunately not so from his parallel down in the social ladder that relegated Wigneswaran to a ground level seating position which itself messages hegemony, control and power domination at national level that comprise the urban Sinhala majority.

Those that are averse to an innovative constitution remain ever so loyal to all such centric concepts, for it is in such that hope rests in gaining political control of this island nation. If the Tamil politicians want to make a success of devolution, it is not the gun that is the best option, but the exposure of such warped and limited minds among the Sinhala politicians before the international arena and continues with such support for constitutional elegance in egalitarianism.

Let the new constitution carry the Buddha’s message of ‘siyalu sathvayo niduk vetwa, duken midetwaa’ (may all beings be devoid of suffering, be well and happy), the very concept conspicuously absent in the ’72 constitution for its exclusion and exclusiveness that renders part of this country’s citizenry suffer discrimination and sorrow. Yet, the blatant irony is the loud proclamation that Buddhism shall be upheld as the religion of the majority, when practice collides with theory that nullifies Lord Buddha’s lofty ideals.

Add new comment