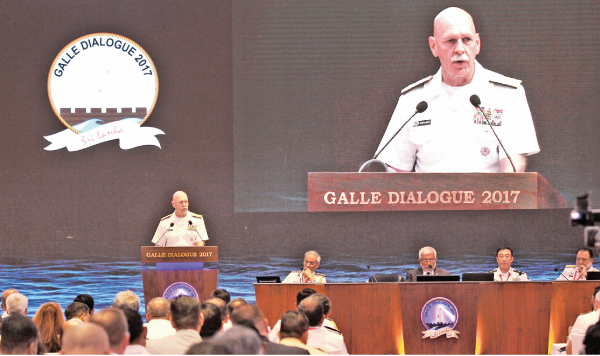

The Galle Dialogue; International Maritime Conference was inaugurated by the Sri Lanka Navy since 2010 under the patronage of the Defence Ministry. At the Galle Dialogue 2017, Admiral Scott Swift emphasized, “Engagement and building trust remains a critical part of maintaining the inclusive security network that sustains the rules-based order and helps protect freedom of the seas for the benefit of all nations.” Admiral Swift also noted, “Just as nations and their maritime forces have the ability to build trust, their actions, like applying national laws in international space, erodes any trust that can be gained by multi-lateral cooperation.”

The Galle Dialogue is one of the critically important venues to discuss key issues among naval and maritime leaders. It is an integral part of the ongoing discourse that is taking place across the region and globe in fora like the Western Pacific Naval Symposium, the Shangri-La Dialogue, and the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium. The fact that the Galle Dialogue had to be moved to this larger venue last year is just one indication of its growing importance not just in the region but across the globe.

I am honoured to be among such an august group of maritime leaders. We have representatives here today from six continents and Oceania, indeed all corners of the globe. More than anything, I think this is a fitting representation of how much the seas connect us. I look forward to learning from the diversity of ideas and the experience present in this room.

| Multilateral operations, exercises, and professional dialogues such as this one today help build habits of cooperation, foster understanding and interoperability between participant forces, and develop allied and partner nation capacity. In short, they build relationships, which in turn produces trust |

As just mentioned, our nations are linked by the sea. For millennia, adventurous men and women have harnessed the winds and ridden the currents to transport merchandise, people, and ideas across the great distances of the seven seas. Those sea routes, established long ago when seasonal monsoon winds governed the age of sail, have empowered the growth and prosperity of nations around the world.

That dynamic is still the case today, where 90 percent of global trade remains dependent upon sea borne transport. In an increasingly interdependent global economy, we share an interest in providing continued security at sea, in order to produce stability, which in turn sets the conditions that allow prosperity, the opportunity to continue to grow.

Indo-Asia-Pacific region

For the last 70 years, the Indo-Asia-Pacific region achieved unprecedented levels of stability and prosperity, due in large part to our collective respect for – and adherence to – international norms, standards, rules, and laws. These bench marks were not imposed by any one nation upon another; rather, they emerged through compromise and consensus, with all states having an equal voice, regardless of size, military strength, or economic power. Since the end of World War II, this system has provided the foundation for protecting access for all to the shared domains, including air, space, cyber, and of course, the maritime domain. Our collective support for its underlying principles has transformed the regional economy in dramatically fruitful ways.

Millions have been lifted out of poverty by the rising tide of prosperity that has benefitted so many nations across the region, and there remains unlimited potential for that growth to continue. That trend, however, is dependent upon our collective ability to reinforce the precepts that uphold that rules-based order.

Early last year, I attended the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium held in Bangladesh, where I remarked at the time that if I stood in the Straits of Malacca looking east into the Western Pacific, I saw a number of prolonged maritime disputes that, if not resolved using established mechanisms and in accordance with international law, had the potential to upend the rules-based system and all the benefit it affords. Worse, divergence from these standards could very well set us back on the destabilizing course centred on the failed premise of might makes right.

At the Western Pacific Naval Symposium in Indonesia just a few months later, informed by the transregional trend of destabilization, I reoriented my rhetorical vantage point to the centre of the Indian Ocean. Looking west into parts of Eastern Europe, the Levant, and the Maghreb, I noted ongoing turmoil in Ukraine, Syria, and Libya.

At the time, I saw those shore-based frictions expanding through maritime pathways to nullify prosperity’s growth in several affected swaths of the Mediterranean and Black Seas. I raised both examples as a cautionary tale regarding the spiraling instability that results from at-sea interactions based on coercion rather than cooperation.

In contrast to the angst encountered on either side of the Indian Ocean, I noted in comparison those nations who ringed its shores were the beneficiaries of its being a sea of tranquility. So I asked the question, why is this? It is informative that nations bordering the Indian Ocean, despite an asymmetry in claimant size, wealth, and influence, they have resolved long-standing maritime border disputes through discourse and dialogue leading to binding arbitration, thereby avoiding the lack of transparency, mistrust, and doubt that has plagued relations in the South China Sea and elsewhere. Healthy competition between Indian Ocean states has been bounded and informed by the international rules-based order, fostering a cooperative security environment to the benefit of the entire sub-region. It is an example we all would be well informed and valued by emulating elsewhere.

Maritime challenges

That cooperation is critical in the maritime domain, where the collective challenges we face require collaborative, inclusive solutions. It comes as no surprise that the same seas that connect us and provide immense opportunities for national prosperity and improved quality of life can also transmit distant fractions and frictions that impinge on security conditions nearer to home.

Considering that the Indian Ocean covers more than 20 percent of the world’s surface, in excess of 28 million square miles, the practical benefits of multilateral collaboration become immediately apparent. Through these waters transits half the world’s container traffic, one-third of bulk cargo transport and nearly two-thirds of global maritime oil trade. Any disruption of this movement has serious strategic implications for a number of nations. But along these same corridors, several enduring maritime challenges, like piracy, smuggling, human trafficking, illegal fishing, and transnational terrorism, seek to exploit the seams of governance, where enforcement of security is problematic, hotly contested, or non-existent. Addressing these challenges demands timely, accurate, and actionable information, along with forces available to respond, but the area is too large and prohibitively costly for one nation to effectively monitor and secure on its own.

In that context, like-minded allies, partners, and friends can reduce the impact of the sea blindness that comes with the tyranny of time and distance, through multilateral efforts like joint patrols and information sharing. Actions like these help improve our collective maritime domain awareness, maximize the effectiveness of limited resources in a large area of operations, and reduce the manoeuvre space for enduring maritime challenges to take root. That’s a nice sound bite, but the ability to operate together and share information requires some level of trust to do so, something that national defense forces are, by nature, hesitant to do. So how do we responsibly overcome that hesitation?

Multilateral operations, exercises, and professional dialogues such as this one today help build habits of cooperation, foster understanding and interoperability between participant forces, and develop allied and partner nation capacity. In short, they build relationships, which in turn produces trust. It’s hard to put a price on trust as a deliverable, but it is an indispensable element in the larger context of regional stability and the rules-based order. It is worth noting that if we’re not building trust, then it’s decaying.

Engagement and building trust remains a critical part of maintaining the inclusive security network that sustains the rules-based order and helps protect freedom of the seas for the benefit of all nations.

When Sri Lanka experienced severe flooding this past May, several nations sent naval forces and provided assistance to aid in disaster response and recovery. It is what responsible navies do, and I commend my fellow naval leaders for their leadership in their decision to provide assistance.

Building trust and cooperation

Just last week, U.S. Pacific Fleet forces joined the Sri Lanka Navy in Trincomalee as part of Exercise CARAT 2017. I look forward to the expansion of our military to military relations through activities like CARAT, both from an interoperability perspective and from a perspective of building trust and cooperation to address multilateral challenges.

As we build trust between our forces, we improve our ability to provide security on a wider scale. Piracy and armed robbery at sea plagued the Western Indian Ocean for an extended period, disrupting the delivery of humanitarian aid to Somalia and threatening the use of critical sea lanes. In 2012 alone, the estimated costs to governments and the shipping industry caused by piracy were nearly $7 billion. It took a collective response by maritime nations and their navies, a U.N. resolution, and adjustments to best practices and policies in the shipping industry to reduce this threat to more manageable levels.

At the Eastern reaches, trilateral patrols joining Indonesian, Malaysian, and Singapore Navies have greatly reduced the number of piracy incidents at sea since patrols began.

Just as nations and their maritime forces have the ability to build trust, their actions, like applying national laws in international space, erodes any trust that can be gained by multi-lateral cooperation.

With these realities creeping into the Indian Ocean, maintaining the Indian Ocean as a sea of tranquility seems increasingly problematic. My concern grows regarding the vectors of instability and unhealthy competition that I see developing along its shores. My sincere hope is that the inclusive conditions here will not succumb to more self-serving inclinations, but will instead export that cooperative spirit that resides in this basin for the benefit of all.

I remain convinced that the promotion of the rules-based order is the best possible way forward for all nations to rise peacefully, confidently, securely, and economically.

I am also convinced that by working together, those nations residing along the Indian Ocean that have put aside considerations of size and strength and instead pursued inclusive dialogue and discourse to resolve their national differences can expand their example to the seas surrounding the Indian Ocean, reversing the current trend seen to the west and to the east. As the Pacific Fleet Commander I look forward to continuing to work closely with like-minded nations, focusing on ensuring the benefits provided by free and open access to the maritime domain are enjoyed by all nations, regardless of size, strength or wealth.

Add new comment