Hours before the start of the 1968 Ashes, news came through from Los Angeles that Senator Robert Kennedy had died, the day after he was shot in his moment of triumph at the California presidential primary. John Arlott welcomed listeners to Test Match Special from Old Trafford “on this sombre morning of world news”. Maybe that was not the precise phrase, but I remember with ringing clarity the Arlottian word “sombre”. It contained a multitude of meanings: that we knew what had happened; that it mattered to us as human beings; and that, in due course – probably over much claret, in Arlott’s case – we would discuss its meaning. But for now the cricket would go on, and that was the business in hand.

Would such an event penetrate a modern cricket TV commentary box? Would the blazered Mammonites even mention it?

There is a fundamental difference between the broadcasting of cricket on radio and on television, and it has grown wider with the years. On TV, the orthodoxy is that This Is Thrilling And It Really Matters, no matter what. On radio, there is a tacit pact with the listener, who will be registering the cricket as an agreeable extra in their own day-to-day routine. The context is whatever else is worrying us, from sick kids to distant assassinations.

When TMS began, 60 years ago, this hardly needed saying. Everyone involved with the game had lived through the war; some who fought were still playing (Keith Miller, who famously described pressure as “a Messerschmitt up your arse”, had just retired); almost all the players had done national service; no one was paid much. Yet cricket remained supreme as the summer game.

Now, many professionals have done little in their lives except play cricket, and get paid well, even if no one has heard of them. TV commentators, who are paid exceedingly well, act as though nothing on the planet is as significant as the umpteenth iteration of a computer’s opinion of an lbw. In the meantime, cricket is disappearing from Britain’s parks, greens and consciousness to its new home, up its own backside.

Against this background, TMS is a miraculous survivor. It is the game’s prime ambassador to the outside world, as it has been since it began, on May 30, 1957. It has changed since then, of course it has. But, unlike the game it serves, it has changed organically, in keeping with its own traditions. Survival rests on a number of happy accidents. One is stability. There have only ever been three producers: Michael Tuke-Hastings for 16 years, Peter Baxter for 34, Adam Mountford for the past decade.

Neil Durden-Smith, now the senior surviving TMS commentator (sounding in his eighties exactly as he did in his thirties), did a handful of Tests in the early 1970s, before concentrating on PR. He remembers how straightforward it all was: “You came into the box in the morning, and there would be a note pinned up with your times, and that’s what you did. You just sat down and got on with it. If you were last on, you had to hand over to Jim Swanton to do the summary. It was very relaxed, very informal.”

Indeed. Tuke-Hastings had a good many other BBC responsibilities, such as producing quizzes. He oversaw the non-London Tests from a distance, as did Baxter in the early days, leaving the on-the-spot role to regional men, including Dick Maddock in the Midlands and an interesting cove in the North called Don Mosey. But the informality had a firm foundation. The basis of TMS is that of all great art: a disciplined line combined with a wild imagination. Shane Warne’s bowling worked the same way. For the commentators, that means describing every ball accurately, giving the score regularly and judging the mood astutely: when to concentrate on the game, and when to discuss last night’s dinner, Blowers’s trousers, or the latest email from Mongolia.

Deviation from those rules can be fatal. Alan Gibson rivalled Arlott in his gifts as a commentator: he had a voice like honey and a marvellous way with words. Like Arlott, he enjoyed a drink; unlike Arlott, he could not judge his intake. He was despatched after a slurred performance at Headingley in 1975.

It was Arlott who created the tone. More than anyone else, he reached out beyond the core audience. People would say – especially women, who were considered tangential to the sport in those distant days – that they liked him “because he didn’t talk about the cricket”. He did, but he made it accessible, using his broad sensibilities, wit and command of metaphor. From 1946, long before TMS brought in ball-by-ball coverage, Arlott set the standard. It did not at first include much hilarity. That didn’t come until Brian Johnston was added to the team in 1966; he joined it full-time when he was booted off TV four years later. Producers said he did not have the discipline to match his words to the pictures. Johnston said: “The emphasis was to be on an analysis of technique and tactics… So be it. But it was not my cup of tea.”

Radio and TV coverage now went in different directions. Johnston’s 24 years on TMS helped encourage the habit (more difficult now that satellites are involved) of turning the radio on and the TV sound down. And when the BBC’s TV coverage finally expired in 1999, it did so – for all Richie Benaud’s brilliance – mainly of boredom.

Yet the idyllic image of choccy cake and old chestnuts in the radio box was not quite accurate. The two stars of the 1970s – Arlott and Johnston – were far from close friends. Arlott and Tuke-Hastings both retired to the island of Alderney (population: 2,000 or so) but did not speak. Mosey, who joined the commentary team in 1974, could start a fight in an empty room. No one who scored as meticulously as Bill Frindall was likely to be happy-go-lucky.

But the upshot was a remarkable creative tension. TMS was a trailblazer both in cricket – its influence yanked Australian commentary away from its old solemnity – and beyond. Brough Scott, host of Channel 4’s once-stylish (and now sadly lost) horse racing, described his programme’s formula as “a mix of Test Match Special and drive time”. Cricket was also a flagship for the dear old wireless itself. Once it was assumed that radio would slowly wither. TMS is one of the reasons it has done no such thing.

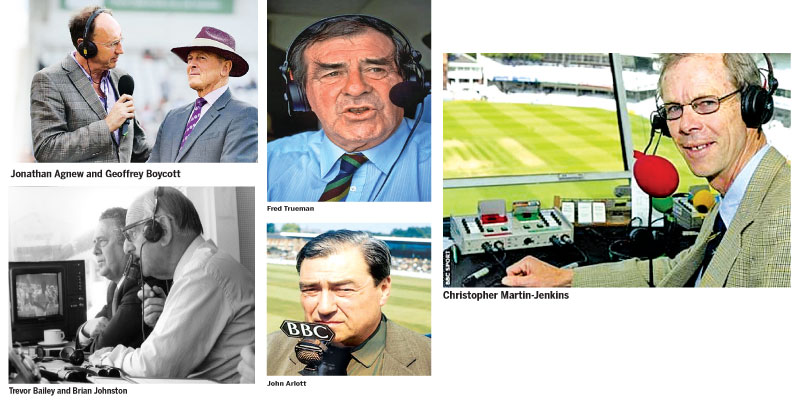

And the programme has had a knack of chance discoveries. On the Saturday of the 1976 Lord’s Test – a rare damp day in that blazing summer – the panel were allowed to keep chatting, instead of handing back to the studio. The BBC found people enjoyed it as much as, or more than, the actual cricket. Jonathan Agnew, an intermittently excellent fast bowler, turned out to be a consistently excellent broadcaster, whose skills and growing stature helped lead the programme almost seamlessly through the deaths of Frindall, Christopher Martin-Jenkins and now Tony Cozier, all well before their powers might have waned.

There was a rocky patch in the mid-to-late 2000s. Clouds appeared during the last years of Baxter’s long, sunny reign in the shape of men in suits who wanted the measured tones of TMS to match the zippier style of Radio 5. The rota had indeed become too much of a closed shop. But Baxter was pushed into giving young men from the sports room their commentary debuts, whether he was convinced by them or not.

Among those was Arlo White, a highly competent broadcaster who was chosen for the post-2005 Ashes tour of Pakistan, and then for a couple of home Tests. White had played for Leicestershire Under-11s, but when he commentated in his head it was on football, and he readily admits he was not exactly Swantonian in his grasp of cricketing lore and history. He was monstered in the press, mainly by the serial controversialist Michael Henderson, whose other TMS victims have included Vic Marks, Ed Smith, Alison Mitchell – and Swanton. “The criticism stung and hurt,” says White. “But I got to see some great places and worked with some of the world’s most talented broadcasters, and I wouldn’t take a second of it back. Anything I do now is based on what I learned on TMS.” He’s fine: chief English soccer commentator for NBC, purveyors of the Premier League to the eager Americans.

Mountford himself seemed to make a shaky start. The commentary team settled down, but the summarisers went a bit haywire. For most of TMS’s life, this role had comprised serial duopolies: Freddie Brown and Norman Yardley; Trevor Bailey and Fred Trueman; Marks and Mike Selvey. Now there was a cacophony of voices, many brought over from Mountford’s previous berth on Radio 5, and not all the voices were any good.

But it fell into place quite rapidly. Mountford had unearthed one diamond: Phil Tufnell, a find he credited to CMJ, who had worked with him in Sri Lanka, and said, “He’s brilliant.” Tufnell, like White, might not be up to speed on Victor Trumper. But his sharp cricket brain and sharper wit have been a huge plus.

For me, there are lingering issues. There is the Geoff Boycott problem. Geoffrey has now discovered that cricket is indeed a team game, and judges it as such; I’m not sure he has cottoned on that the same applies to commentary. There also seems to me too much movement in and out of the box, too many different voices in too short a time, the key changes stifling the melody.

Mountford insists this is unavoidable. “For years Peter just had to do a list. Now it’s more like a jigsaw puzzle. I’ve got so many other outlets to worry about. They’re dodging to 5 Live, Radio 1, Radio 2. They might have to nip out of the ground to do TV news, because we don’t have the rights, and the cameras are not allowed in. The big change is social media. I might have to get Graeme Swann or Michael Vaughan to do half an hour on Facebook, taking questions from the audience.”

But on the whole TMS is in rude health. Mountford hears nothing but support from the BBC hierarchy. It is said British emigres to France settled in the Dordogne because that was the most southerly place with reliable reception of Radio 4 Long Wave. Now the internet takes it across the planet.

Though Frindall was the master statistician of his generation, he had no love of computers and no patience with weird stats. Andrew Samson and his extraordinary database give radio the lead in off-the-wall facts: “Player most often out for two in a one-day international? Just wait a moment.” Women, led by Alison Mitchell, are in the box on their merits and on equal terms.

The most interesting commentator of the new generation is Daniel Norcross, who made his Test debut at Edgbaston last summer. The route to commentary now is usually a slow progress through the BBC ranks (Simon Mann and Mitchell), or playing (Smith), or both (Charlie Dagnall). Norcross made a living for a while playing pub quiz machines, had a spell in the City, and drifted in and out of dot-com jobs before setting up Test Match Sofa, an anarchic internet-based non-rival to the real TMS: a group of blokes watching TV and chatting, with the ECB going berserk and accusing them of destroying the world of sporting media rights. “It was the most fun, the most silly enterprise I have ever been involved with,” he says. “I was doing the one thing I had always wanted to do, even though I had none of the qualifications to do it.”

He finally wrote a hopeless gissa-job letter to Mountford, who had a hunch Norcross could do it. I think so too: he has knowledge, enthusiasm and a smile in his voice. And, like the policeman/poet Arlott, an unusual perspective. Even more improbable is the one-day scorer Andy Zaltzman. It is not unusual for TMS to be a route into comedy gigs; Zaltzman has done it the other way round. But he is a serious scorer nonetheless.

In his last years, I got to know Rex Alston, the straight-man commentator of the early TMS. He was a classic public-school master of his generation: benign and humorous, but deeply conservative. He would have been startled out of his wits by the clown-haired Zaltzman. But they are both legitimate members of a great tradition.

I was standing by the school dining hall when I heard Arlott say “sombre”. While I was listening to Norcross make his debut 48 years later, I was chopping thistles. I heard England beat West Indies at Lord’s in 2000 from the car park at a niece’s wedding. Funny how these associations remain in the mind more readily than the Tests one actually saw.

For others, it can be even more important. “Thank you, TMS,” a listener in Ankara wrote last year. “You’ve meant more than cricket for us.” It has never been more vital to our game, and our lives. – The Telegraph

Add new comment