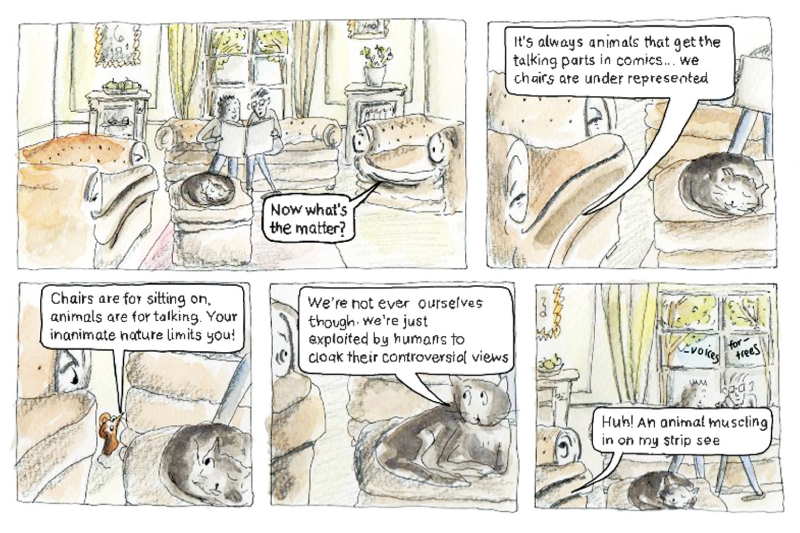

Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus tells the story of the author’s parents, Vladek and Anja Spiegelman, from their first meeting in pre-war Poland to their survival of the death camps at Auschwitz and Dachau. It is largely responsible for transforming the way we think about comics. Published in two volumes in 1986 and 1992, having initially been serialized in the magazine Raw, it was the first graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize; it also became a publishing phenomenon, selling over two million copies worldwide. A defining feature is its portrayal of the characters as animals: the Jews are mice, the Germans cats, the Poles pigs and the Americans dogs. Of course, Spiegelman was not the first person to use visual anthropomorphization to critique society, and in particular to draw attention to its malevolent elements. By the eighteenth century there was already a rich tradition in Britain and Europe of using animals in satirical cartooning and caricature as a means of ridiculing power and the powerful, and pointing out moral ills through humour while avoiding libel. James Gillray (1756–1815) often used animals to create venomous representations of politicians, such as the depiction of Charles James Fox as a human figure with a fox’s head and brush. In literature animals have a long history of use as a device for social comment, from Aesop’s Fables to Gulliver’s Travels (1726).

Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus tells the story of the author’s parents, Vladek and Anja Spiegelman, from their first meeting in pre-war Poland to their survival of the death camps at Auschwitz and Dachau. It is largely responsible for transforming the way we think about comics. Published in two volumes in 1986 and 1992, having initially been serialized in the magazine Raw, it was the first graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize; it also became a publishing phenomenon, selling over two million copies worldwide. A defining feature is its portrayal of the characters as animals: the Jews are mice, the Germans cats, the Poles pigs and the Americans dogs. Of course, Spiegelman was not the first person to use visual anthropomorphization to critique society, and in particular to draw attention to its malevolent elements. By the eighteenth century there was already a rich tradition in Britain and Europe of using animals in satirical cartooning and caricature as a means of ridiculing power and the powerful, and pointing out moral ills through humour while avoiding libel. James Gillray (1756–1815) often used animals to create venomous representations of politicians, such as the depiction of Charles James Fox as a human figure with a fox’s head and brush. In literature animals have a long history of use as a device for social comment, from Aesop’s Fables to Gulliver’s Travels (1726).

The historical associations of combining cartoon animals with humour contributed to the difficulty Spiegelman faced in convincing a publisher to produce Maus as a book. In Metamaus (2011), which looked back at the making of Maus, Spiegelman recalled rejections from publishers including Penguin, Henry Holt and Knopf. The author’s approach was apparently viewed as trivializing – a risk publishers were hesitant to take. Penguin’s Gerald Howard explained his rebuff as “to do with the natural nervousness one has in publishing something so very new and possibly (to some people) off-putting”.

Spiegelman’s masterstroke, however, was to use this tragicomic combination to intensify his work’s central message, while satisfying a readerly demand for both levity and gravity. This was reinforced by his artistic approach, which expresses seriousness through simplicity: his decision to sacrifice colour in favour of a simple black-and-white style, for example, highlighted the darkness of the subject, thereby allowing him to avoid gratuitous representations of death and suffering.

The emotions in Maus are generally communicated through facial expression, often captured with minimal line work, while Spiegelman added personalization through the hand-drawn quality of his lines in both text and images.

- Times Literary Supplement

Add new comment